Blue Prince (For a Revolution)

Chance-based games as exercises of anti-indoctrination and political discovery.

Despite society's best efforts to convince us otherwise, every part of our lives is subject to chance. Try as we might to influence our social standing, financial security, mental well-being, or physical health, there are simply too many variables at play to guarantee that we will be the person we want to be at any given time. No act of mindful living will protect you with complete certainty from layoffs, car accidents, house fires, cancer, climate change, war, stochastic terrorism, an icy patch on the sidewalk, fraud, market failure, grief, heartbreak, or political jackknifing, and yet we are all urged to crawl ever upward as if perfect self-definition is as much an inevitability as chance.

Although few would consciously verbalize this, one part of the meteoric popularity of video games is the opportunity they afford players to reify and experiment with chance. Innumerable probabilities are hashed out input to input, moment to moment, informed, for example, reflexively by frame data in an action game, or after deliberate mathematical consideration in a turn-based RPG. Decisions can safely be made one after another in these hermetic spaces. Successful ones gratify us, unsuccessful ones often disappoint and frustrate but ultimately pave the way for more closely considered decisions in the future. We are allowed a multiplicity of avenues through which to test our impulses against the vagaries of chance, and, liberated from real consequence, to find pleasure and amusement even when these impulses fail us.

Or at least we were. Mainstream expectations for video games have taken a clearer shape than ever, a familiar smooth shape that every other medium and platform has also grown to take: total frictionlessness disguised as quality of life. In the 2025 market paradigm, RNG is often a mere suggestion, brushed off if the number thus generated is found wanting. Consider the current state of the Fire Emblem franchise, the last three games of which include penalty-free time rewind features in case something goes wrong. Or perhaps Atlus' Unicorn Overlord, an heir to the Ogre Battle games that tells you the exact result of every combat before it begins and allows you to manipulate a variety of factors until you've arrived at a more satisfactory conclusion. Even Baldur's Gate 3, nominally based on a dice-heavy tabletop game that needs no introduction, is a milquetoast Dungeon Master falling over itself to offer you rerolls and long rests and cheap resurrections. Three venerable franchises are renovated with industry-sanctioned risk aversion at the forefront, each change justified in the popular eye with one rhetorical silver bullet: "it's saving me time, so what's the problem?"

Moving past the easy, fatuous argument that video games are fundamentally a waste of time no matter how you're playing them, the glaring issue is the implicit assumption that "saved time" is an absolute virtue. This mindset is a consequence of overexposure to modern game design's love for robust, extrinsic reward systems; having to load a save from fifteen minutes ago after a fatal mistake stands in opposition to this. Those fifteen minutes are lost – ex nihilo nihil fit – and expecting a player to self-salve merely with the wisdom to not repeat the mistake is a long bet for any developer with a product to sell. In response, many modern RPGs now let you replay a battle immediately upon defeat to mitigate lost time, roguelites sweeten each failed run with new skills and baubles, and even FromSoft lets you try and get your souls back. The mutual expectation that all of a player's spent time should have an immediate, demonstrable result is runoff from capitalist logic, a weaponization of managerial-suite expectations demanding productivity. Why would you ever do something when the possibility exists to receive nothing in return? Why even entertain that possibility at all? And so games feed ever more into the great lie of the social contract: chance is no match for our ability to bend the system to our will.

Enter Blue Prince.

"When I inherited Mount Holly, I never had to prove myself. They just gave me the keys and left it at that... I never really had any goals or objectives to strive toward. I never had any dreams to realize." - Herbert S. Sinclair

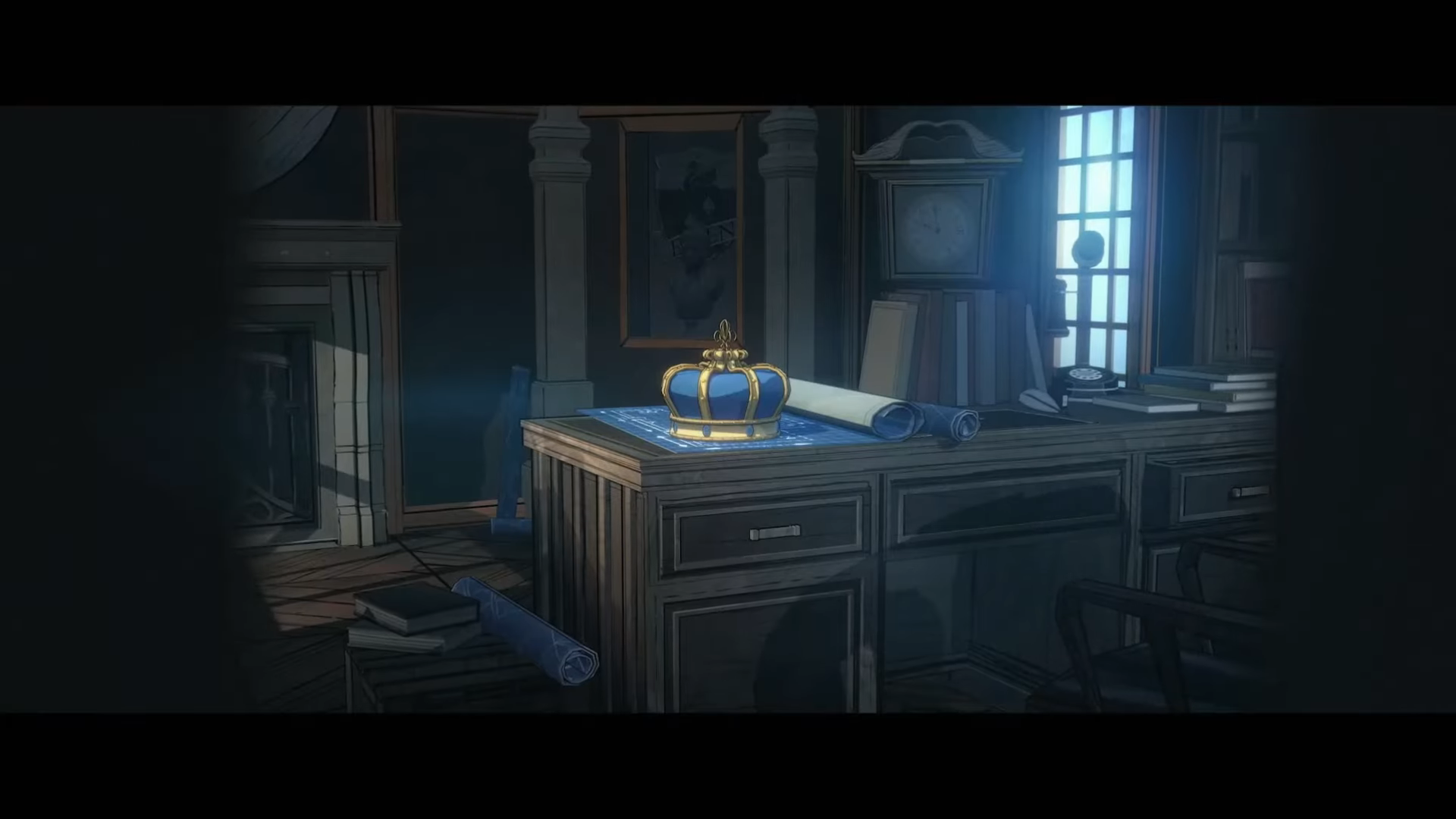

Simon Jones is a 14-year-old boy. He's not a silent protagonist, though he's about as close as you can possibly get to being one. He has been selected to inherit the vast Mount Holly estate from his prankster granduncle, assuming he can solve a series of riddles and find its hidden 46th room. The catch: at the end of each day, the estate's form slips into nothingness and Simon must draft it anew the next day, room by room.

Chance introduces itself in Blue Prince immediately, unavoidably, and inexplicably. There is no effort to ease the player into any ludonarrative explanation for this house's quicksilver walls, merely scattered confirmations that yes, it is this way for everyone. Likewise, there is no way for the player to evade the reality that much of what they achieve is transitory, either washed away completely or not always suited for what tomorrow might bring. "[I]t is very important to me that you 'start fresh' each morning and not rely on the successes of the previous day," Herbert tells his grandnephew in the only letter he's guaranteed to see. The chance is the point.

Some of Simon's successes do follow him, of course, beyond just the acquisition of knowledge and experience. You gain permanent resources: stars, allowance, increases to your starting stamina, new rooms; you can find items that apply modifications to rooms; you can deploy rooms and items that help to influence what other rooms and items become available to you and when; you can connect certain parts of the estate to others, creating shortcuts and safe passages; all of this, in concert, creates an arsenal meant to help you fight against the RNG but never vanquish it. None of this will ever totally quell the agita of having to build the house from scratch, wracked with anticipation over whatever new shape will keep you from pulling at a thread you absolutely must follow. The curious player, however, will come to see each trip through Mount Holly as a journey of discovery, an eternally unfolding invitation to take notes and experiment, the thrill of the chase more valuable than any accumulated resource could be.

The presence of RNG here is understandably divisive. This game has upset and disappointed a fair few people. It thumbs its nose at the celebration of single-minded A-to-B goalposting that quest-based gaming has inculcated in us over the last decade+ by making many of its "quests" inaccessible at the blink of an eye. For all of the concessions extended to Simon, there are just as many ways for them to fail him: you don't get the item you need; you don't draft the room you need; you have everything you need but you're not sure how to solve the puzzle yet; you don't even have a lead so you might as well draft and sleep and draft and sleep until something clicks. For some players it is enough to search for meaning in riddles, and for others it is enough to wrangle a warping shape one loop after another, but Blue Prince makes a daunting, enormous chimera of the two, and not all of those players want to stare that down.

It's tempting to concede to their indignation by acknowledging that every gamer has a unique set of thresholds for different strains of ludic friction, and that subjective experience is as valuable a foundation as any for critique. Giving discursive primacy to the individual experience unavoidably overshadows the collective one, however, and the chance to observe how this medium can point us toward a common perspective with tactically employed friction is lost when we assume that it's valid to ignore or demonize friction altogether. This strategy is available to us in the real world, as well: turn inward, away from what troubles you. Escapism is a familiar outlet for gamers, but it's rarely a productive one. Little new is learned from the familiar, but instead from our efforts to understand the inscrutable circumstances that chance presents to us. Maturity, developing knowledge, comes with drawing associations and finding patterns in seemingly unrelated circumstances, those that may be forced upon us by, for instance, day-to-day life in a sociopolitical sphere that we have little control over. We cannot count on the resources we have on hand to be there forever, or to be exactly what we need to overcome a challenge that faces us; every day in this world is different, and may require us to call on what we might never have expected the day before. We will never be able to recognize this capacity in one another, or in ourselves, if we only ever turn inward.

Our protagonist, Simon, again, is only 14. The world has not heretofore expected maturity of him. His mother, children's book author and missing political dissident Mary Jones, certainly didn't when she published The Red Prince, a cheeky tale about a young royal who hates every color but red. The first version of the book you'll likely find in Mount Holly concludes by handing the titular prince his own copy of The Red Prince that he can retreat into whenever he's confronted with a non-red color: "A story about you, / if it needs to be said. / About a red prince and his book. / The red book, we just read." In this form, it is superficially charming but retrogressive, an endorsement of single-minded escapism (turning inward). A second version found in a less common room is identical but includes a hidden note from Mary to Herbert: "they made me change the ending of course, as you predicted." Between this note, the rejection letter from her publisher in the attic, and the intimations of contentious regional history dotted throughout the estate, it becomes apparent that some political subtext was squashed out of the book.

The political becomes intertwined with the personal once Simon reaches Room 46. A cutscene follows in which Mary reads her original version of The Red Prince, her voice set to glimpses of a younger Simon: poring over the very same book with a red paper crown atop his head, posing for a family picture in his smart red sweater, gazing at his dejected mother in the middle of a political rally splashed in conspicuous red. This draft paints the prince's obsession with red as blinkering, an excuse to close himself off from "life's many symphonies." The final shots of the cutscene show Simon gazing into Room 46, his eyes falling upon a blue crown:

But one day,

the prince saw something new,

And if you look closely,

you might see it too.

The skies parted

And the clouds withdrew.

The prince had a new favorite color...

the color blue.

Credits. And yet the game has only just begun.

Blue Prince is, among many other things, a coming of age tale about a young man learning the truth of the world he lives in. This cutscene transforms Mary's book into a political allegory and presents Simon as THE Red Prince, raised deep in the throes of indoctrination, who, before being entrusted with the circumstances behind his mother's disappearance, must first grow to understand that the world is not always what we want it to be. To this end, Herbert Sinclair, an accomplice to Mary's subversive activities, subjects Simon to the transformative potential of games and riddles. Once Simon demonstrates the ability to play within and thus look beyond the limits imposed by the propagandistic regime in which he was raised, his path to greater revelation unfolds.

All play, by definition, is circumscribed within a series of limitations, each game an entreaty to make what we can of what we are given. Limitations create the parameters by which we must all approach a shared space. They are a direct rebuke to the capitalist notion that some people deserve free rein over our world by virtue of class or genetics or ability. Political education, likewise, is not a matter of "knowing" everything right out of the gate. No one is born with perfect morals or perfect awareness; we are all subject to our randomly selected childhoods and the larger cultural context in which they are situated. To be mindful of our world despite this requires diligence, focus, patience, and a willingness to tear out beliefs that you previously held and replace them with something new. These values exemplify the flexibility absent in the fascist mindset that the game decries. As Herbert's Mount Holly asks them of Simon, so too does Blue Prince ask them of us, and they cannot be tested for if the answers are simply presented to Simon or the player. To this end, the game functions as a kind of anti-power fantasy. It does not strictly disempower the player, as a horror game might do, but instead weaponizes chance to remind them that power is generated within the self as a necessary response to friction. Once again, as in real life, we must identify, develop, and act upon patterns as a way of moving forward when no other way presents itself, and oftentimes in Blue Prince the limitations imposed by the aleatory structure necessitate exploration and experimentation that we might not otherwise be inclined toward.

This is why Tonda Ros' choice to tell this story within the framework of a puzzle game is so exceptional. Working your way through a puzzle, problem, or dilemma is how you self-actualize, and what could be more of a puzzle than repeatedly seeking truth in an impossible space? Blue Prince's perpetual randomness and the variability of its multi-pronged mysteries ensures that there are a tremendous number of ways to pass through it, and that no two people will do so in the same way. Strategies that work for Player A may not for Player B, and Player A's crawl-up-the-walls headscratcher may come totally naturally to player B. A person's ideation is fundamentally unique, situated in their mind alone. Contrary to what an oppressive regime might insist upon, there is no one best way to move through this world, so long as we remain willing to see the full spectrum of its opportunities. Our minds are a gift that can only be colonized if we allow them to be.

But then that's what those regimes are counting on: the ability to colonize us, to smooth us out by presenting easy answers, and to stamp out any thought that stands in the way of productive uniformity. To belabor how this manifests in our world is beyond this piece's scope, but the oppressor so depicted in Blue Prince, as well as the stage for the events of the game, is the self-proclaimed "militaristic" nation Fenn Aries. Fenn Aries emerged 130 years prior to the events of the game when a group of nobles from the Grand City of Fenn, disgusted by the populist largesse of Orinda Aries' King Desilets III, took advantage of a change in power to mount an offensive and seize control of the region for themselves. After a war lasting well over twenty years, the Fenn nobles deposed the Orindian monarchy and installed their own king, renaming the region in the image of their Grand City and enjoying an uncontested rule spanning up to the present day.

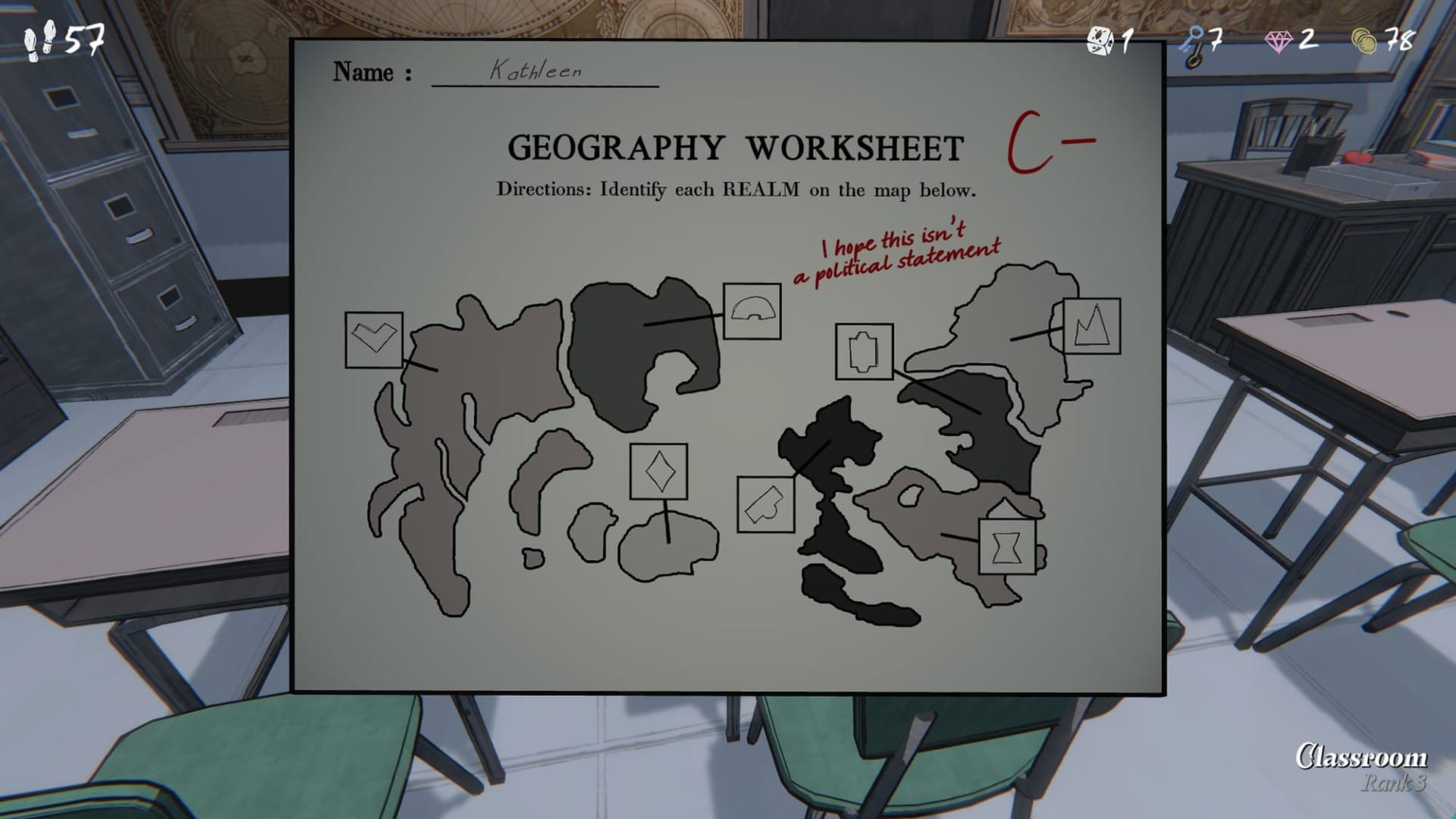

To maintain authority, of course, a political body must instill loyalty in its subjects, and the Mount Holly Estate was put to this purpose by the government by serving as a site for its schoolhouse for nearly forty years. While the game presents little information about what was taught in the tiny Schoolhouse, the interim Classrooms that Herbert hosted in the residence during the construction of the new school in nearby Reddington are substantially more damning. Red flags adorn each room, children's geography worksheets are dotted with ominous suggestions to adhere to political orthodoxy, and a slide projector flickers between idealized Romantic paintings of coronation ceremonies and violent warfare and Fenn Aries' politically-motivated destruction of the international rail system. "History is penned by the victors" is plastered on the wall of the sixth-grade Classroom. Every first grader says their favorite color is red. Every fifth grader correctly answers the quiz question about how it's forbidden to fly the black flag of Orindia.

Once the player has observed the foundation of political education in Fenn Aries, the intimations of more widespread cultural control found in numerous rooms begin to make more sense. A book of Orindian history in the Library has been heavily redacted by the Fenn Aries Central Board of Education, in ways that distort the meaning of the text: King Desilets III was depicted in its first edition as "a king who was often seen among the people eating, drinking and conversing," but with a few strokes of a black pen became "a king who was often seen [...] drinking." Local newspaper The Reddington Herald makes no attempt to curb its biased pro-monarchist language, casting its reportage of terrorist bombings and tensions with neighboring countries into question. And then there are, of course, the notes alluding to the Red Guard, Fenn Aries' cultural police force, who spent at least one day stomping around Mount Holly in an attempt to uncover dirt on Mary's subversive activities – or Mary herself – despite having little more evidence than her children's books.

While these glimpses into totalitarianism provide important insight to the current state of Fenn Aries, it's also important to consider them as deliberately-placed objects within Mount Holly, both by Herbert Sinclair and Tonda Ros. Although the estate was always an ever-shifting puzzle box, Sinclair made substantial changes to it, working frantically even in the days before his death, in order to tailor it specifically to the experience he wanted for Simon. Everything there (with the possible exception of some recesses so deep and curiosities so hidden that Herbert himself may not know of them) is arranged such that there is no doubt what Herbert wished to communicate as the impetus for presenting Simon's inheritance as a puzzle. Both diegetically and by the nature of creating a narrative video game, game-making is presented unequivocally as a form of authorship.

But then what differentiates this from the propaganda that Fenn Aries impresses upon its citizenry? Are Sinclair and Mary not authors of a similar strain of political persuasion that they are attempting to impress upon Simon? The crucial distinction is that while the Fenn Aries regime attempts to completely revise history and present that revision as a singular reality, the Mount Holly challenge, and Blue Prince as a whole, are unabashed works of simulation. For all of the "real world" political antagonism the props dotted throughout the estate allude to, Herbert created his puzzle with no pretense that the representation of the larger political climate therein is a document of complete truth. The Classrooms, for instance, are temporary copies, and the Locked Exhibit simulates Mary's theft of the seized crown of Orinda Aries with a paper facsimile, protected by cardboard guards and a fake security system. By intermingling spaces like these with other spaces that provided a true political purpose – the Shelter, the Safehouse, and eventually, one learns, the Throne Room that confirms the estate to have been built atop the ruins of Castle Orindia – the metaphorical is used to contextualize and give shape to the real. Every randomized reconfiguration of these elements is a new invitation for Simon not to turn inward, but to consider the state of his home and the fight over its soul that his mother and great-uncle participated in.

Herbert's approach represents the best of what any work of art can hope for in attempting to convey a political message. His manor establishes its parameters, its "magic circle," and once Simon has learned to adapt to its rules and solve its initial challenge, everything afterwards is subject to his interpretation. This is the attitude with which Herbert and Mary prepare him for the injustices of the adult world, by confronting him with a puzzle which itself contains an artifact, a historical truth, and a revelation about his birthright, all of which in concert grant him the kind of power we can only hope the mature might use responsibly. Blue Prince itself is structured the same way: everything before the credits apprises us of a surface-level mechanical and narrative complexity, and everything after invites us to iterate upon our understanding of that complexity to see what greater depths the game has to offer. Indeed, we approach all art as a vessel for meaning in a similar fashion, first by applying a linear logic as a means of parsing its rules and structure, and then shifting to a more abstract logic to determine how the structure as viewed in total informs the work's overall aims. Blue Prince is exceptional insofar as its use of its medium to delineate its linear and abstract phases is so thorough, and its transition between the two so natural and ludonarratively justified, that the political emerges as a matter of both the player and Simon simultaneously "seeing something new" within Room 46. Unless the player is locked in merely for the sake of increasingly difficult puzzles, there is no way to miss the emotional resonance of a story about a boy opening his eyes to the cruel world that swallowed up his mother.

This narrative strategy grants us the context we need to unravel and comprehend its primary emotional thrust: Mary's master plan to assemble a group of political dissidents, marshal them to forcibly reclaim the crown of Orinda Aries from Fenn Aries, and disappear before the state can punish them. Why so much effort for what ultimately amounts to a symbolic victory? Well, isn't a player's victory within a video game symbolic? Why do we go through so much effort for those? Life, like a game, asks us to stare down many unexpected challenges with no reward but the sheer catharsis of crawling through to the other side. The only reward for Mary's perilous scheme is that despite her inevitable exile, her separation from her son and the land she loves, and the ire she invokes from Fenn Aries, she finally has a symbol more powerful than children's books to convey her values to a young person in whom she sees the future. "Explain to him, if you can, the intersection between foolishness and doctrine," she beseeches Herbert in a letter written about a year after the heist. Simon's reward for reaching Room 46, an ordeal organized by a riddler's own flair for foolishness and doctrine, is the opportunity to finally pull back the curtain on what could possibly be so important to demand these grave sacrifices. That opportunity can be ours, too; we need only ask ourselves why we are being so challenged, and what those challenges are meant to point us toward.

Even this approach, however, has its limitations, which Blue Prince attempts to reckon with in its own unique language. The game's roguelite genre shell means that it has closing credits but no true ending, no point at which the player is gently told to put down the controller. The closest it comes is in a room tucked deeply away in the estate, likely to not be discovered until dozens of hours after Room 46 has been uncovered. Within this room is a permutation of an earlier logic puzzle that asks the player to determine which of three boxes contains a prize by using the statement on each box's lid. Invariably, one of the statements is a lie, one is a truth, and the third could be either. In this case, they read:

1, blue) You have reached the end of your journey.

2, white) There are two true boxes in this room.

3, black) There is no end to this journey.

The blue box contains a draft of a children's book called The Blue Prince, written by Mary under her real name rather than her pen name and dedicated to Simon. True to its name, it's a variant of The Red Prince, featuring a lad who's obsessed with blue ("He seldom talked to others, / for they rarely shared this view. / He never went to town, / Nor saw the flags they flew") and plays a game to help him avoid the other colors of the world ("It was a game full of rooms / and the stories that we climb, / About a house full of lies / and the truth that one prince finds.") Although the book's fanciful tone and illustrations are inviting as always, the game also uses it to implicate itself by casting this Blue Prince in the same light as the closed-minded Red Prince, a cautionary metacommentary to be mindful of what we are losing ourselves in and the world outside of it. Rather than allowing Blue Prince to become an escapist totem to the same fascism it decries, we and Simon have to leave the magic circle eventually if we want its story to have meaning.

The white box is empty. Nothing happens when the player opens it.

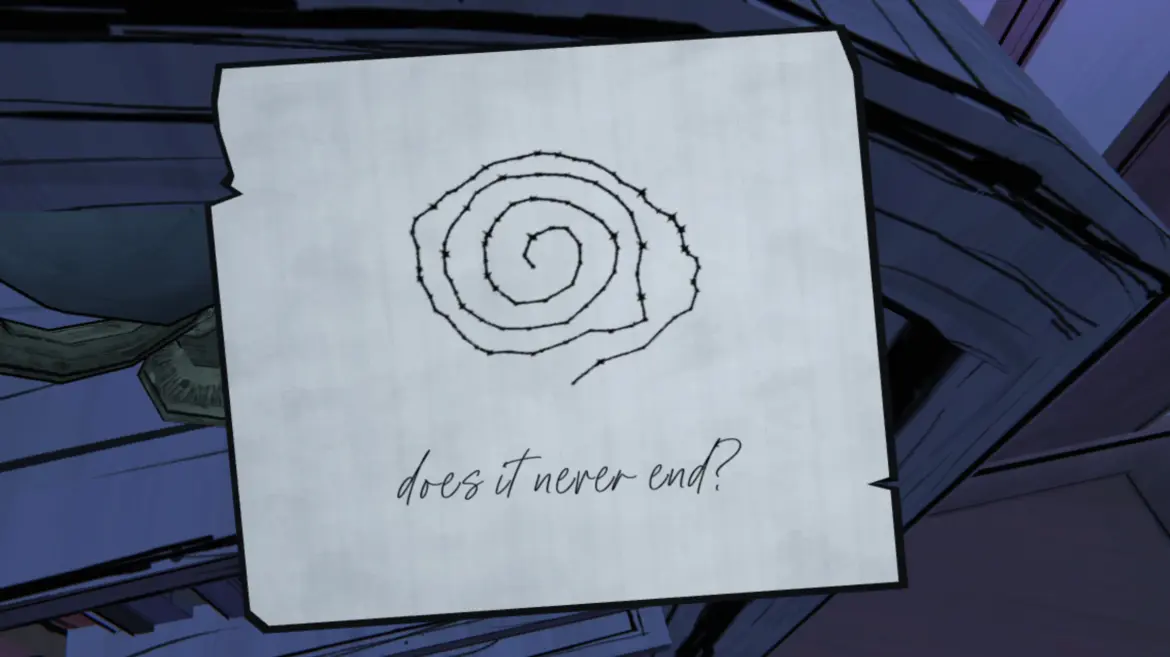

The black box triggers a cutscene in which Simon slowly opens the box only to reveal, once again, that it is empty, save for a spiral on the inside of the lid. He looks over to the blue box, then ruefully back down to the black box, before the screen fades to black.

To spare ourselves the step-by-step deductive reasoning, let's skip straight to this puzzle's claim: statement 2 dictates that there is no logical way for statement 1 and statement 3 to both be true or both be false per the rules of this game. They are directly opposed to one another. Statement 1, and the book underneath it, offer the cleaner answer, an exhortation to let go of the game and continue our journey in the real world. It is a respectable thought for a video game to close on, though certainly not an unprecedented one... and if you consider the note hidden on one of The Blue Prince's pages repeating an earlier message that the true box does not always contain the prize, not necessarily a definitive one, either.

Statement 3's grander implications seem contradicted, at least in Simon's disappointed eyes, by the empty box that accompanies it. That very emptiness, however, that lack of meaning, IS the meaning. A journey with no end, by definition, has nothing to offer. A story with the time and space to say everything is just an empty box, waiting for you to put whatever you want inside. The combinatoric wealth enabled by the game's structure allows for endless play, but it cannot grant endless meaning to it; a boundary must be drawn, a limitation created. Rather than present endlessness as an incorrect answer, however, Blue Prince reminds us one last time that there is a finality in acknowledging that we cannot know what lies ahead, and that we cannot ever align a set of variables so perfectly that the world appears before us in full truth and splendor. This "endless" game tells us here that it is unable to make the meaning its Blue Princes seek, that there is no symbol it could put in the box that would tie the past and future of this endeavor together, and thus the burden falls upon them to take what they have learned and use it to keep chasing what they now know to be a forever spiral. Chance springs eternal, and only when we are given more rich platforms like Blue Prince's world through which to embrace it will we be able to stand informed and unafraid against its inevitability in ours.

"At my age, I often find myself looking back at the long path behind me, and I think I am content to leave a few stones unturned. A life without some mystery is a life without imagination. So, I will lay down this burden and leave this stone, and the winding path of intrigue it precedes, for future generations to explore." – Herbert S. Sinclair

Stop Caring is reader supported and 100% free. Please consider subscribing or making a one-time donation to make more of this possible. All donations on this article go directly to the author.