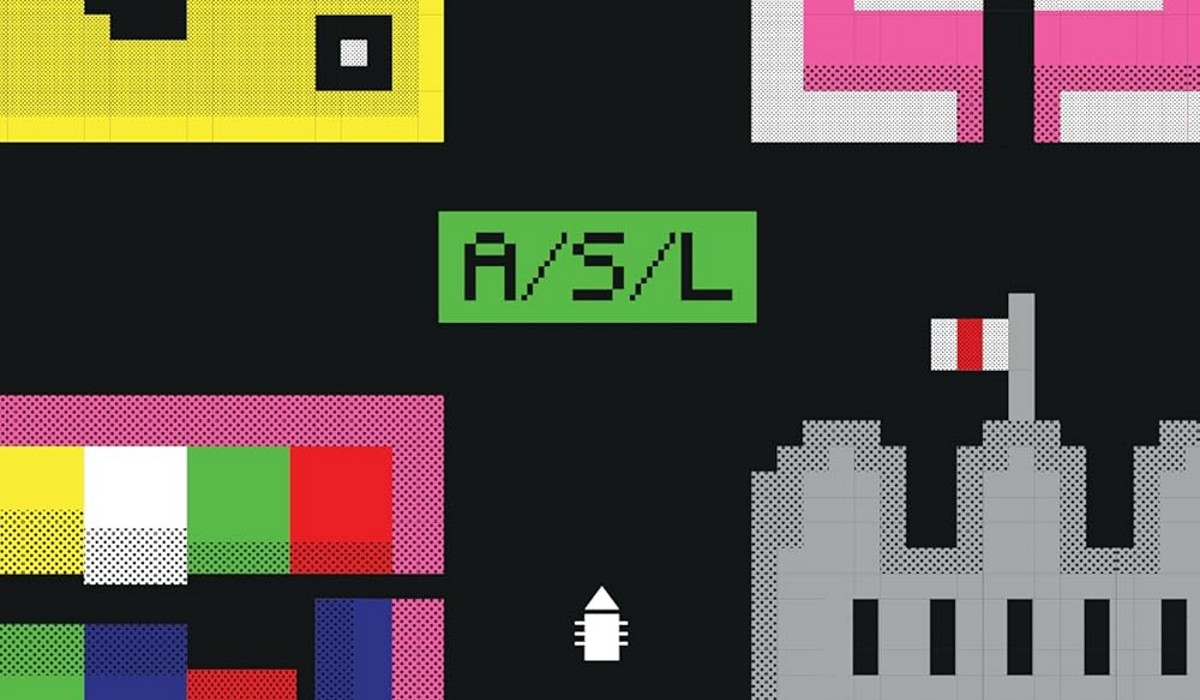

A/S/L: Jeanne Thornton's Saga of the Sorceress

Long live ZZT

This piece is based on an interview with Jeanne Thornton. Answers have been edited for clarity and content.

It’s 1998, and Abraxa, Sash and Lilith are three teenagers making a game together in CraftQ. Their project, Saga of the Sorceress, will be like no game the engine has ever seen. Inspired by the Mystic Knights series of console roleplaying games, Saga of the Sorceress will feature over twenty dungeons, a custom soundtrack, and over a hundred cutscenes rendered in ASCII art. But it is never finished. Abraxa and Lilith disappear from the CraftQ community; in response, Sash dissolves her corporation, Invocation LLC.

Now it is 2016. Abraxa is staying with her friend Marcie after a freelance job goes horribly wrong. Sash lives with her parents and does online sex work for cash. Lilith was just promoted at her job at Dollarwise Investments. They have not heard from each other in eighteen years; the only thing that unites them is that all three are trans women. Yet, the game they worked on back then still haunts them. It is a gleaming UFO buried in the sediment of their lives, shaping their thoughts and actions whether or not they are aware of it. Might Saga of the Sorceress one day be realized?

Jeanne Thornton’s A/S/L is a novel about game making, but not the kind you might be used to. The game developers of our imaginations, like Shigeru Miyamoto or John Romero, were like rock star gods conjuring lightning from the dark of the heavens. Their creations changed the lives of millions of people. Abraxa, Sash and Lilith aren’t like that. They made games in hobbyist communities. Even had they finished Saga of the Sorceress, they’d be lucky if a hundred people played it.

Hobbyist development seems invisible compared to the omnipresence of commercial game development today, but it is a much older discipline. As Em Reed wrote on their blog back in April, “video games didn’t start as an industry, they started as timetheft by programmers in university, government and military labs who were meant to be doing something else.” What were early computer games like Rogue but hobbyist projects, developed for the sake of it rather than for business purposes?

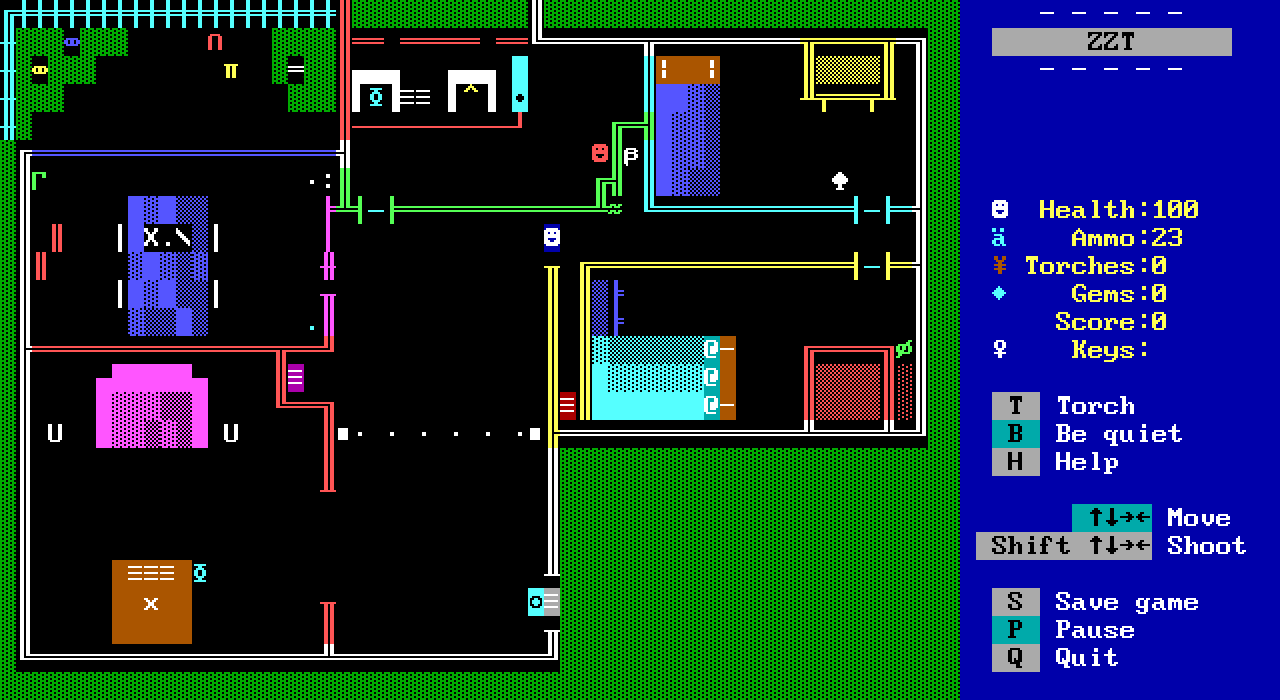

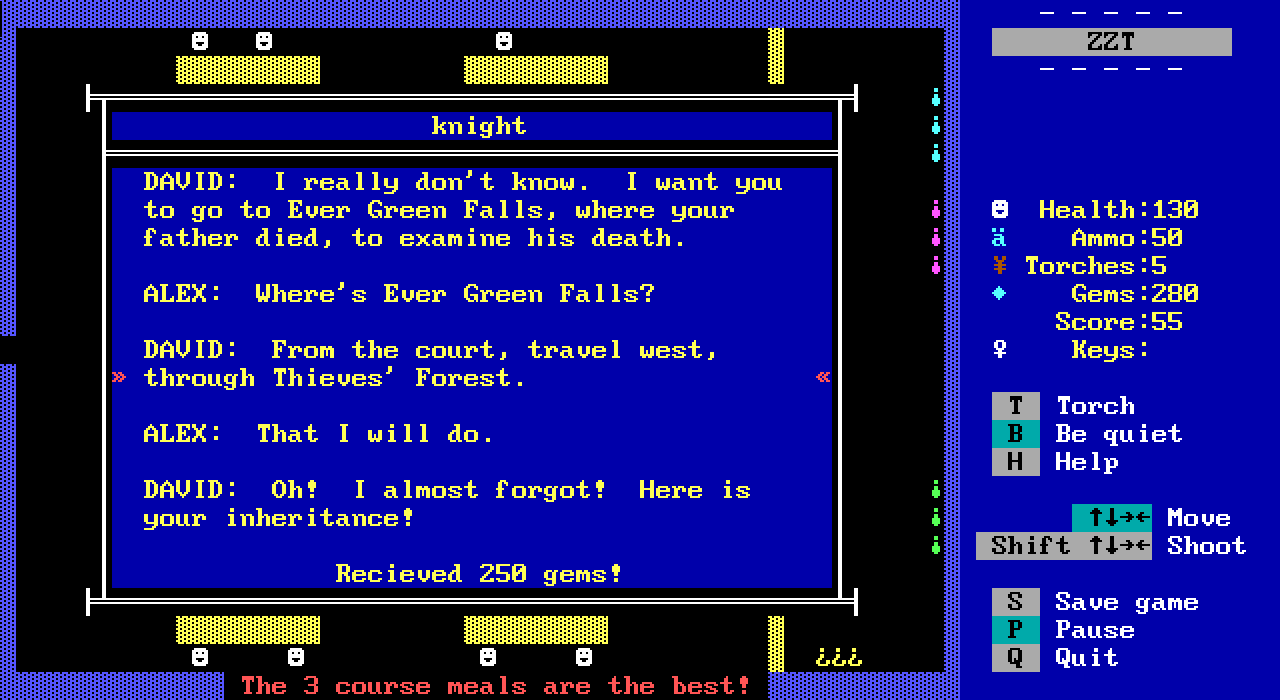

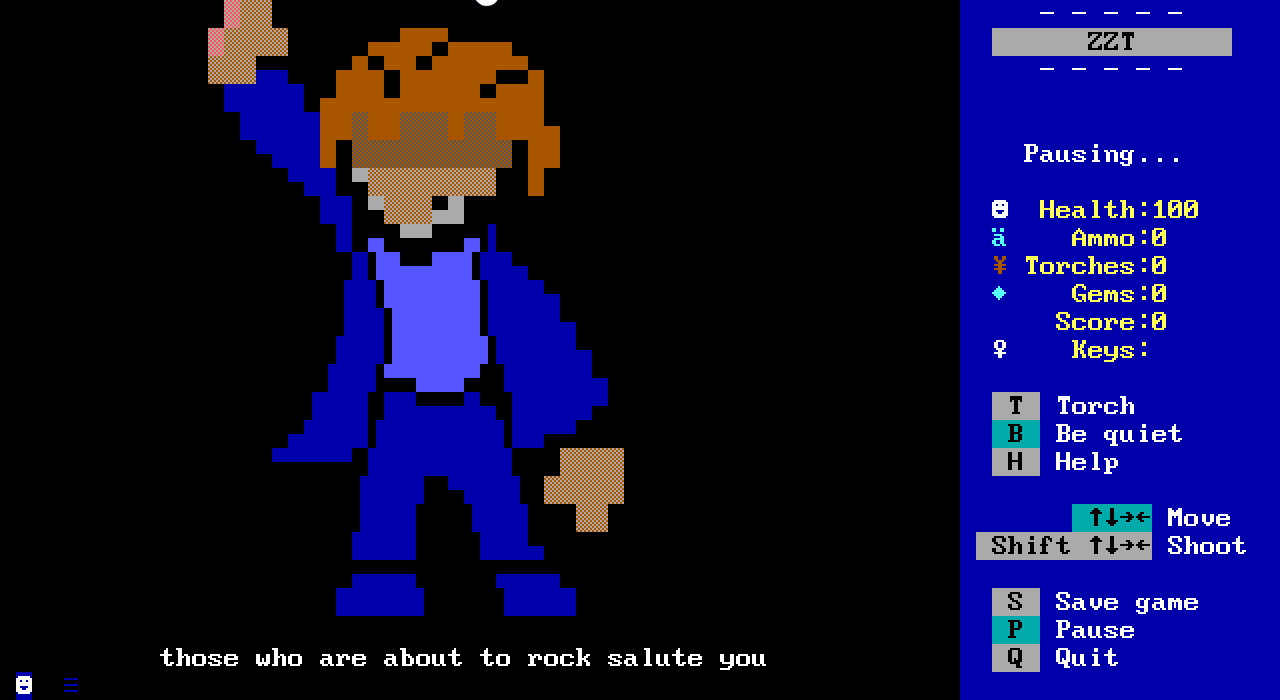

A/S/L’s game-making engine CraftQ is modelled on ZZT, released by future Epic Games founder, Tim Sweeney, back in 1991. The program was antiquated even at the time. Graphics were limited to just 256 ASCII characters with eight foreground colors and 16 background colors. Despite its restrictions, it was simple to jump into ZZT and make a small game without coding knowledge. Anything more complex led to headaches. But that didn’t stop people from trying.

“I remember the first thing I downloaded online was a Lisa Simpson animated cursor,” Jeanne Thornton said to me. “The second thing was a ZZT game.” Jeanne was searching AOL for a game based on the comic Calvin and Hobbes. She found a toboggan racer, which drew her into the ZZT community and inspired her to make her own games. ZZT became the chief artistic outlet of her teenage years, just as CraftQ was for the heroines of A/S/L.

Game development for Thornton was both a communal effort and an individual enterprise. After catching people’s attention with her Rhygar trilogy of adventure games, she was recruited to a virtual magazine called Damaged Incorporated. Unlike modern chain games, in which each developer creates their own segment, Damaged really was a magazine: a succession of textbox blurbs representing each contributor. “People would alternate making Damaged,” she said. “You’d email everybody and ask what they wanted to say in the game…there was one where Sepiroth was stalking us.” Just what you’d expect from a community of teenagers in the late 1990s.

In 1998, a ZZT developer who went by the handle draco released a game called Hollywood Hooker. (According to Thornton, draco was an inspiration for the brilliant but mercurial Abraxa in A/S/L.) Hollywood Hooker was technically advanced, like Grand Theft Auto recreated in miniature within the ZZT engine. But AOL refused to host it, so the community jumped ship for greener pastures. To follow them, Thornton learned how to use IRC. As she says, “I picked up a shocking amount of what I know about computers from ZZT.”

While Thornton has not released a ZZT game in some time, the connections she made in the community remain a part of her life. As she told me, “I was hanging out on Monday with someone I know from ZZT. I got a job where my boss was somebody I knew from ZZT.” She helped copyedit Anna Anthropy’s book on ZZT, published via Boss Fight Books. And she’s friends with folks in other hobbyist communities as well, like OHRPGCE developer Caoimhe Harlock (who co-created the ambitious, Final Fantasy-inspired Spellshard: The Black Crown of Horgoth.)

A/S/L isn’t just a novel about Thornton’s close peers, though. It’s about the people who disappeared, the ones “who are no longer with us and making games, or who didn’t finish them.” For every community legend like Alexis Janson who became professional game developers, there are others who vanished. Only their games remain–whether as complete works or as forum posts or screenshots. That’s assuming, of course, that these works escaped link rot. (Thankfully, sites like the Museum of ZZT now preserve these games from the dessication of the internet.)

“You see people who are completely talented,” Thornton said, “unbelievably skilled in what they do, and then they don’t do anything with it.” Combing through interviews with past community members proves Thornton right; for every ZZT developer who plans to keep making games, there is another committed to retirement. Many of these folks (even the active developers) have day jobs and families now. ZZT is just a part of their life, and perhaps not even the most significant one.

Why tell the story of these communities at all? Game historians tend to cover epochal titles like Final Fantasy VII. Big bets by ambitious developers that succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The producer of Final Fantasy VII, Hironobu Sakaguchi, went on to make another bet with the film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, and failed miserably. That’s another kind of tale, what Thornton calls “the story of thwarted genius and success,” which attracts its own dedicated historians.

Thornton herself has past experience retelling tales of thwarted genius. Her novel Summer Fun reimagined the story of The Beach Boys and their infamous shelved album Smile as a trans narrative. Her heroine B—- embraces womanhood and stakes it on the album of her life. The end of her story mirrors reality, and yet (just like A/S/L) it feels haunted by the ghost of some greater truth. If Summer Fun or Smile really did come out, would it have changed everything?

The stakes of A/S/L are so much smaller by comparison. Abraxa, Sash and Lilith do not have B—-’s resources. Their game is not a potential bestselling album but instead a small if ambitious project developed for a close-knit hobbyist community. Finishing Saga of the Sorceress will not earn them fame or fortune. “If they actually completed the game,” Thornton says, “their lives wouldn’t be different except psychologically. Maybe ten kids would know who they were.”

As if to reflect this, each of the novel’s heroines is a different kind of ghost. Abraxa still practices art, but the world has no place for her; she bounces from freelance employment to couchsitting to homelessness. Sash still dreams the grand visions that fueled her as a teen, but is terrified of writing any of them down. Lilith doesn’t make or even play games anymore, but she carries the lessons she learned from the medium with her: how to move within space, how to make others like her. As far as she knows, she is an impostor; nobody else in her daily life needed these lessons, and any one of them could turn on her at any time.

Thornton took inspiration from the 2016 visual novel We Know the Devil when structuring A/S/L; each part includes two characters and leaves one out. The book’s three heroines are defined as much by their absence from each other’s lives as by their presence. Abraxa and Lilith don’t know each other well; their love and admiration for Sash is all that connects them. The scenes in which these characters share the same space add up to less than a hundred pages of an almost 500 page book. For the bulk of the story, they are alone.

Even if these women had made a game the size of Final Fantasy VII, would that have changed anything? Games have their limitations too. Thornton remembers avoiding local kids so that she could finish Dragon Quest. The process of entering an unfamiliar dungeon, and overcoming it, became a metaphor that meant something to her. She came to recognize the same sense of friction while drawing and while learning Japanese. But there was a lot that didn’t fit, and sooner or later she had to find other metaphors outside RPGs. The stale, self-congratulatory logistics of inevitable self-improvement through level grinding was no longer sufficient.

But art can change people, no matter how small it might seem. “These works you put out into the world create their own gravity or tides,” Thornton says. “Other people will ride on them.” One of those people, Thornton remembers, confessed to her that they brought a character she wrote to talk about with their therapist. “I still can’t get over it,” Thornton told me.

Then there’s trans literature as a whole, with which Thornton’s novel exists in conversation. It is an ever-evolving scene that includes authors across genres and stylistic boundaries. Some of them are published by big publishers like Penguin Random House; others self-publish their work as if they were ZZT or CraftQ developers. Big or small, professional or hobbyist, they carry “something stronger than any individual artist, a set of assumptions that can travel back and forth so quickly.”

Thornton is a self-admitted reader of Rachel Pollack, a tarot expert and genre fiction author. Pollack saw ritual as art, and art as change, a sword cutting through stagnation. Summer Fun reflects Pollack’s influence; much of it is narrated not by B—- but by Gala, a young occultist who works at a hostel in New Mexico. The novel itself can be read as a magic spell she is casting, a counter-history to our own crueler history that is told on her terms.

A/S/L is similarly influenced by occultism. Abraxa sees Saga of the Sorceress as not just programming, but a ritual that she is performing in the world. She is influenced by the Mystic Knights games, which Sash claims had occult and queer themes that were paved over for the English release. In reality, Sash was lying; she made up the “secret history” of the Mystic Knights series because she thought it was more interesting. But that doesn’t mean it was false. Abraxa breathes life into Sash’s lie and makes it real.

That’s the real Saga of the Sorceress: a story of small artists shaping their dreams from raw, unforgiving earth. What remains from those days? A lingering hum, like magic or radioactivity. “Games are places that you can go to and be moved by,” Thornton says, “like an abandoned mall.” But the spirit of ZZT isn’t dead. People are still making tiny games and posting them on the internet as we speak, whether by bitsy, Ren’py, Megazeux or ZZT itself. To quote Lilith: “there is all kinds of newness that has nothing to do with where we’ve been.”

Stop Caring is reader supported and 100% free. Please consider subscribing or making a one-time donation to make more of this possible. All donations on this article go directly to the author.