The Killer Is Happy / The Killer Feels Nothing

Now we're playing with violence. How does the killer feel?

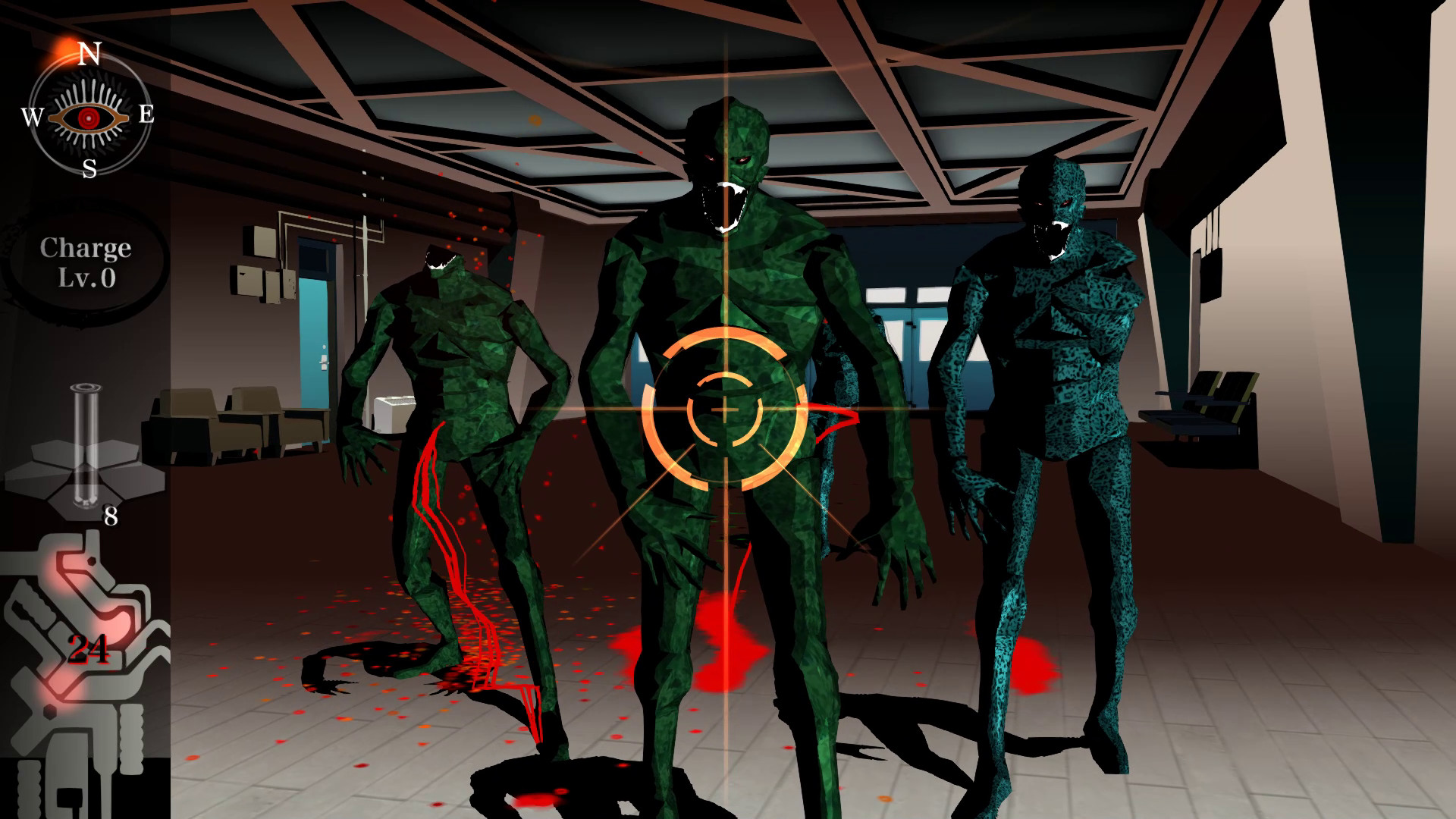

A cleaner carries seven assassins in his cranium – the silver suitcase is for his duties. A snicker; stand by; scanning for threats. A smiling figure loses its invisible cloak and slowly approaches. We're in a tight spot! Shoot it where it glows and the creature explodes into red mist – or is it the atoms of blood? The killer reconstitutes his matter and dons a new face from a selection of seven. None of them are smiling. The only ones laughing are the terrorists.

Plenty of words have been poured into our computer screens on Grasshopper Manufacture's Killer7. Some claim it as the platonic ideal of a 'style over substance' game; some state that, while the story might seem nonsensical, it is a surreal oddity worthy of artistic praise; then there's the faffing about over the post-punk aesthetics and game design of its "auteur developer", Suda51 (as if games are the mind-children of a single artistic genius and not a collaborative effort between multiple parties, but I digress).

I would argue that there's too much substance in Killer7 – so much that it poses a gargantuan task to try to dissect all the thematic layers. Peel away at how the game converses with terrorism, surreal spirituality, the artificial divides of East/West, and you'll still be far from its core.

Ultimately, Killer7 is a game about violence. About the banality of the personal violence we commit and react to, as well as the cynical nature of geopolitical warfare that sees countries and their inhabitants as pawns on a chessboard – to be sacrificed, used and erased as deemed necessary. More than that, it's a game that exposes how killers might feel - how they walk a wobbly line of apathy and joy when they let the red blood pool from the bullet holes they've formed.

Videogames are cultural objects that necessitate an action of 'play' - it is only through the act of 'playing' that one can experience videogames, and alongside that playfulness, they are adopted (for the most part) with a joyful nature. It is not a controversial statement to make - violent videogames can be fun.

The violence inflicted in virtual worlds is divorced from real-world consequences - the idea that videogames incite players with aggression is pseudo-scientific conservative drivel - but the violence displayed on our computer or TV screens is, still, a mirror to the world. Videogames are reflections of the human cultural spirit, and violence is quotidian for many of us, especially those of us who live on the margins of society. And we bring our own violence, our perceptions of it, into the game.

It feels odd to define Killer7 as 'playful', what with its mechanical rigidity, as the shooting doesn't necessarily feel joyful with the restrictiveness of its gameplay - its on-rails shoot-em-ups that posits violence as a straight path with only two directions, headfirst into the massacre, or away from it.

Yet, I am happy when executing bloody slaughter in Killer7. I am smoking a dopamine pipe when my shots hit the glowing orbs and the Smiles evaporate into globules. I am ecstatic when my bullets connect to soft tendon and my character lets out an audible "Phew! You're fucked!" alongside a satisfied sigh. This is the act of 'playing' in pure-form. Childlike, even, despite its brutality.

Killer7 shows us the process and aftermath of killing in all its complexities and absurdities. The laissez-faire attitude we exemplify when we pull a virtual or real trigger, the joy we might get when a right bastard gets shot down, when we play with violence, and the ghosts that haunt us and remain...for something always remains, and resurfaces, like bile in your stomach easing its way up your throat. It always comes at the most inopportune moment.

The message that Killer7 concludes with, after navigating through all of its bullshit (affectionately), is, ultimately, a very simple yet powerful assertion: if you kill enough, you will be desensitized to violence. You will feel nothing. In certain moments, apathy opens the way for joy - but even then, that happiness, with its playfulness, is marked by something sinister that will make itself known. Soon, your lost sensitivity starts crawling back and will leave you paralyzed in shock. By that point, it will already be too late.

Killer7 often portrays violence in apathetic and cynical ways, especially when occupying the shoes of the killers. The Smith Syndicate, the main characters of the game, are a group of contract killers working for the US government - either that or the splintered personalities of a single person, and since Grasshopper Manufacture spells out very little to the player, even whose personality is at the center is under question. It could easily be the moribund, wheelchair-bound Harman or the group's 'cleaner' Garcian, who collects the bloody, paper-bagged remains of his fallen comrades in order to have the player revive them with furious button-smashing.

The seven killers showcase few emotions outside of a certain detachment from their actions. Even the more playful of the bunch - Con with his yahoo attitude, Mask de Smith with his immediate, almost naive, trust in others, Dan's sarcastic quips and remarks - still act as people completely desensitized to the act of killing.

No moment represents the indifference the killers feel better than the fourth mission of the game: Encounter.

The killer7 are on the hunt for Curtis Blackburn - a former contract killer for the American Government and Dan Smith's mentor. His crimes are abhorrent and include human and organ trafficking, mostly harvested from the bodies of children. As soon as the government has no more use for him, he goes rogue to continue his illicit business on the side of the Heaven Smiles.

After a Western-style standoff, synced with the flight of a white dove, Dan emerges victorious. With his dying breath, Curtis asks Dan what he makes of his 'little hobby'. Dan responds:

What do I think? I think that what you got here is no different than what those guys do at immigration.

This line hit particularly hard in my recent replay - it invoked the current political struggle in the United States, what with ICE agents gestapo-style kidnapping immigrants and US citizens. There really is no difference between what Curtis and Immigration Services do when looked at on a surface level: both are about dealing in humans as products. Both deny the implicit humanity we all have. Both treat humans as cargo.

There's a certain playful apathy attached to Curtis' words too - he calls his criminal enterprise a 'hobby', an act of personal pleasure. He gets joy from this. I wonder if ICE agents feel joy when they separate families or send innocents to prison camps. I wonder if they enjoy it. I wonder if they feel anything at all.

There is no personal beef resolved - Dan executes his former mentor because it's his job, and he does so with the same lethargy he exemplifies when he guns down any Heaven Smile. Sure, he calls Curtis a 'sick maniac', but Dan is just as depraved. They are both vicious killers.

This scene proves a point about fatal violence: that it is often bigger than the dichotomy of the killer/victim. As agents of the United States, all the violence committed by the killer7 is geopolitical in nature - every dead Smile or target is another body for the USA to climb over in order to retain its top position in the global hegemony.

The apathy of the killer7 is contrasted with the explosive joy of your adversaries. The existential threat of this antagonistic force is that a virus can make us ecstatic while it turns us into suicide bombers. That we can be overjoyed with the promise of extreme violence.

The lessons Killer7 reflects about real-world violence is that weird paradox - that violence is a complex enough action, so firmly rooted to its own contexts, that it is reasonable to expect such varied responses of apathy and joy.

Killer7 always connects the violence you perform to broader political contexts - it always led me to thinking of violence in wider terms, thinking about how killers must feel with all this.

Killer7 exaggerates geopolitics into inane situations where decisions that affect millions are made while those involved are 'playing'. A table of politicians play Mahjong before they shoot each other in the head. Two immortal forces play chess in a secret room. A hitman for the government and his handler look over a bridge while rockets fly to devastate a foreign country - and they're enjoying the 'fireworks'. It is a game to them - it is playful.

Killer7 is a cultural product informed by a post-9/11 world. It invokes notorious acts of terrorism, and a culture obsessed with them, with its imagery: there's the aforementioned self-exploding nature of the Smiles, reminiscent of suicide bombers, but they can take many forms, such as a plane that zigzags towards the player, for example. Take a gander at Travis' shirts, too. Travis is one of the various helpful ghosts that haunt the Killer7. He serves as a mechanism for exposition, always providing information on the various targets you're hunting and the behind-the-scenes political happenings. In the final level, he dons shirts with the names of cities that had infamous terror attacks. Bali. Naples. Nairobi. New York.

Terrorism is, in itself, its own complex action. More often than not, a terrorist attack is a direct response to structural or political issues - a reaction to U.S. invasions, post-colonialism, or an act of desperate self-determination. Terrorism, whatever opinion one might have about it, is still a brutal act of violence and its promotion in global media makes us all spectators to the carnage.

The terrorists that form Heaven Smiles are killers too, and in severe contrast to the killer7, they do exude playfulness and joy. This metastructural dissonance - when the virtual enemies I am facing are closer to representing how I feel when I play violent videogames - is the main trap by which Killer7 exposes violence in all its complexities.

Playing a game, feeling joy in violence, elation when a Nazi fucking dies - none of this is apathy. This is why I was often attached to the Heaven Smiles - they're the only ones having any fun at all! They're the only ones who laugh and 'play' with the Killer7 - who are, in essence, a band of thugs for the U.S.A.

The terrorists reach absurd levels of playful performance - from the zany, half-decapitated Japanese politicians that dabble in slapstick during their boss fight, to the full-on anime girls you fight, magic-girl-style intros and all.

When we joke about lives lost in 9/11, when we celebrate a certain Luigi (from the Mario Bros.) who shot King Bowser in the back with bullets marked by three D-letter words everyone who's ever been fucked by healthcare knows - how is our joy not a response to the sanctity of human life the rich and powerful take for granted? In the same way, how are the Heaven Smiles not a consequence of US imperial hegemony and warmongering, even in this absurd virtual world that posits Japan as an equal superpower (and threat) to the United States? Both are real and appropriate (not necessarily moral, but logical) responses to geopolitical violence.

Violence is, and forever will be, a burden. It is easy to laugh, to play, to engage in the 'theatrics' of violence when one is not a killer - when one is the subject of violence and not the executor of such. As much as Killer7 broadens conversations of violence, it ends by hyper-focusing on how killing affects people on an individual level - in its climax, it shows what happens when killers have a moment of consciousness, along with the pain and devastation that it brings.

In Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing, the filmmaker documents Anwar Congo and his accomplices as they dramatically re-enact and explain, in vivid detail, their involvement in the 1965-66 Indonesian mass killing of communists, or those suspected of harboring 'communist thought'. The movie serves as a useful parallel to Killer7, for in this film the feelings of the killer are front and center - and they constantly change, mold and shift.

They start by detailing the various murders and tortures they've committed with detachment and apathy - they talk about kidnapping communist parents and leaving their children crying and screaming. They often laugh and joke about their murders - they happily show the film crew the spots where they would take supposed Communists and execute them, joking and laughing all the way. They even engage very strictly in theatrics, as the filmmaker asks them to set up a play in which some of the killers will play the part of their victims.

In the same way the killer7 are haunted by ghosts, so too is Anwar cursed - early in the film, he details the nightmares that keep him up at night. The sounds of children screaming, flashbacks of his murders, memories of killing.

It is only when Anwar is forced to play the role of one of his victims, that his empathy triggers. He has a panic attack and calls off the whole performance. He takes the film crew back to the rooftop where he executed dozens if not hundreds of innocent civilians, and he breaks down. He cries. He throws up. The killer feels something after all. But only after the damage is done.

In the last level of the game, the truth is revealed to Garcian Smith. Not only did he kill the original killer7, but he's been programmed from a tender age to be the perfect assassin for Japanese imperialists - so that he may strike from behind enemy lines. He even learns his real name - Emir Parkreiner - and rediscovers his deep psychological scars. Indoctrinated to kill for the Japanese, he rebelled against his instructors and murdered most of them, joining up afterwards with the American government, to seek revenge against those that molded him into what he is. His psyche is broken - all his memories lost, his personalities splintered. Ironically, he became what he least wanted to be - a pawn for government forces. A killer.

He defends himself multiple times in the game - he shies away from the act of killing and reaffirms his role as a 'cleaner'. In the character select screen, he quips:

Don't make me say it again. I'm a cleaner.

'I'm a cleaner'. Not a killer. Yet, he also states:

I can feel no remorse when seeing a dead body. To me it's merely cold rotting flesh.

The apathy of the killer in full effect. No regret. A dead body is a lump of flesh - not a former human.

He is the most important member of the syndicate, as his death is the only one that can cause a game over. Because of this, the player rarely takes control of him - the rest of the assassins are more combat focused. Garcian is there, essentially, in the role of a healer, to revive the rest as they fall.

After a surreal journey, Emir's blood-soaked path ends when he stands face-to-face with his younger self, who then places a gun in his mouth and pulls the trigger. Emir/Garcian is left alone, on the roof of a building, same as Anwar, full of regret. Longing for his wasted youth. Longing to return to being just a 'cleaner', not a killer.

He cries:

No...It wasn't me...It can't be...It's all a misunderstanding...

He opens his silver suitcase, and sees all of the guns the killer7 uses. Dan's revolver, Mask's grenade launcher, Kaede's pistol. All these gunmen are dead by his hand, and he took from them a part of their soul - internalized them all into different personalities. There is no killer7, there is only one lonely assassin. He has no friends, no comrades. No family. Just like Anwar at the end, he falls to the floor and cries. He is left alone with his devastation, accompanied only by the spirits of those he murdered, forevermore.

A killer carries seven assassins in his cranium - he no longer carries a silver suitcase. His palm holds a golden gun. His forehead blossoms into an eye. And he weeps. The killer feels something after all.

Stop Caring is reader supported and 100% free. Please consider subscribing or making a one-time donation to make more of this possible. All donations on this article go directly to the author.

If you are interested in writing for Stop Caring, please reach out via the email listed on the contact page or dm Artemis on Blue Sky. Stop Caring offers compensation, loads of creative freedom, and no deadlines. All it asks for in return is open communication, no pieces that promote discrimination against vulnerable groups, and please, for the love of God, leave that AI shit at the door.