No Good Options

And damn it, we are gonna figure something out, if it takes me all night.

CW: Depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation.

"God, it is just us talking now, and I worry about everything I can’t control. God, can you tell me how much longer I’ll get to be alive and in love. God, I am sorry for the times I didn’t want to stick around. God, there is a scroll of things I have taken for granted in order to survive this long, and it is endless." - Hanif Abdurraqib, On Seatbelts and Sunsets

Often, when I am struck with the awareness of my sinking into the freezing depths of depression and suicidal ideation, I turn to art that reflects it. It could be self destructive. It could make my sobs heavier, my tears denser, my arms wrapped tighter around my knees. But it helps to make it hurt less.

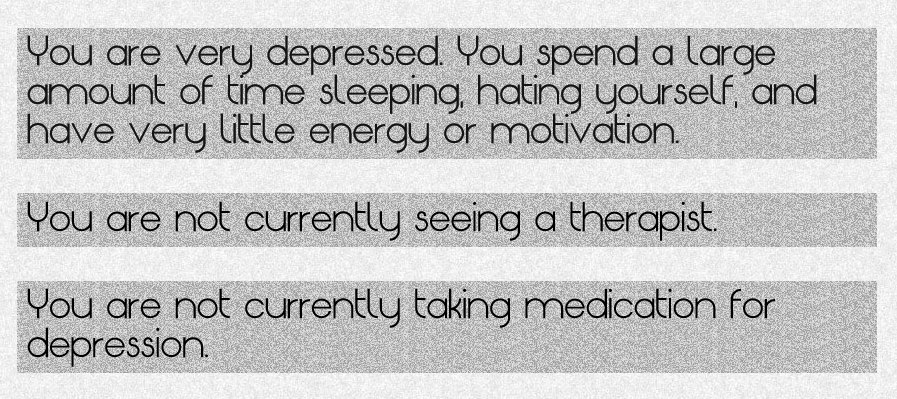

‘Depression Quest is a game that deals with living with depression in a very literal way. The game is not meant to be a fun or lighthearted experience.’ These are the first words you read upon opening 2013’s Depression Quest — Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey and Isaac Shandler’s interactive experience of mental illness and eventual cultural phenomenon. These words are unapologetically accurate.

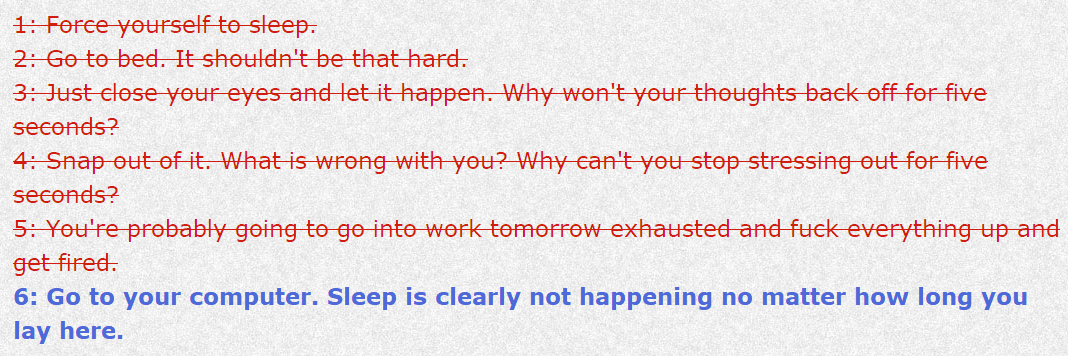

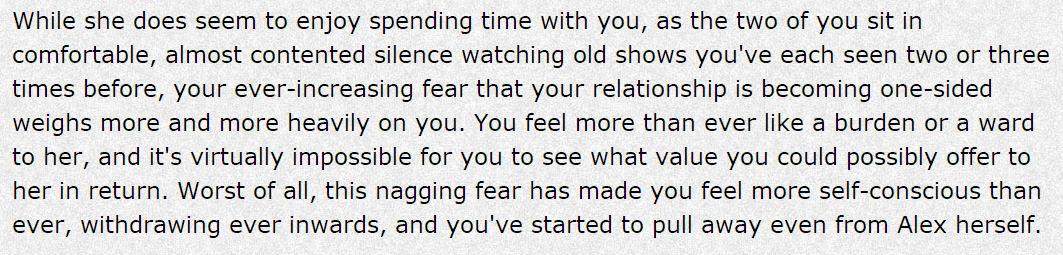

In an interview with Playboy, Quinn noted their interest in games that “aren’t there to make the player feel exceptional.” Depression Quest takes this intention much further than the player being just unexceptional, though; the player/protagonist is actively unable to perform what would be considered by many to be basic, day-to-day mundane tasks. The expected structure of interactive fiction is torn apart as positive choices are ripped from your hands before you can even consider their appeal: speaking to strangers at a party; making the choice to sleep when their body calls for it; talking to their partner about their emotions. It all seems doable, in a vacuum. But that’s depression. Actions that aren’t self-destructive become utterly herculean prospects, requiring internal strength you simply do not possess. There are no good options.

You wish for these choices to be made available, to scrub away the red pen forbidding them, with the same fervour one may have wished for Sephiroth’s blade to miss Aerith’s navel. Always a question of what could have been. But there are no Whispers here, no will of the planet to keep things the way they should be, on the right path. There’s just you, the prospect of better choices, a better life, and the feeling of drowning.

There’s a sardonic humour in the existence of Steam guides for the game that offer tips on how to get the ‘good’ ending, often in the quickest way possible, with the lowest quantity of clicks. One, by user 空梦残月in帝都, describes itself as a ‘Simple guide for a quick pass’ in Depression Quest, but also sweetly states “I think it is still productive for the depression in real life.” Isn’t a quick and easy route out of depression what we all wish for?

Wait, no. I phrased that poorly.

Either way, we don’t get an easy way out. We grasp the few options we have and try to make the best of them. My most beloved writing on this struggle, Hanif Abdurraqib’s 2018 essay On Seatbelts and Sunsets, is about Julien Baker’s track ‘Hurt Less’ from her album Turn Out The Lights, released the previous year. But it also isn’t. On Seatbelts and Sunsets is a painful reflection on death both deliberate and divinely intervened, acts of God, acts of love, the difficult act of choosing to live and what is lost when you choose not to. Abdurraqib notes ‘Look, it ain’t nobody’s job to keep any of us alive other than ourselves, and I get that.’ He’s right, obviously. But maybe we need to want to be alive to not take an easy way out; to make any choice that betters it in the first place. And maybe it’s nobody’s job, but it helps to make it hurt less.

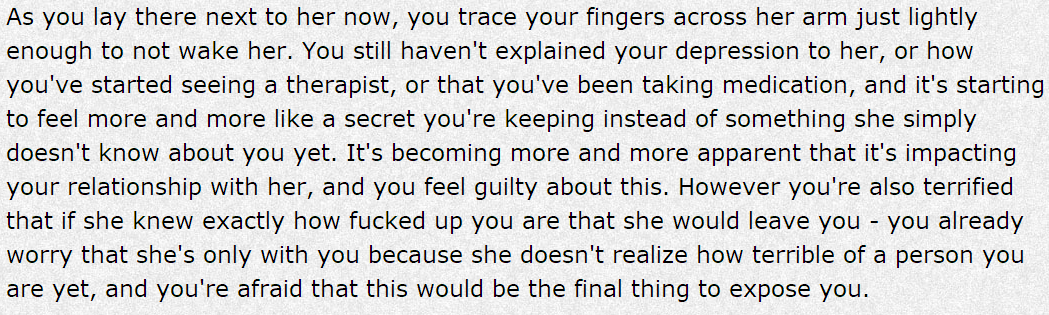

Depression Quest’s vision of being loved while sick is what we would all beg on our bruised knees for. Being loved even when neither you nor your lover know how to help. Even through the debilitating fear of loss upon this beautiful, perfect human being hearing your utter failure to exist as one — ‘There’s no way someone could deal with how you really are.’ It’s a familiar fear.

Alex, the protagonist’s partner, truly wants to be there for them, even if not in a position to fix them. Maybe it’s not her job to keep them alive, but she’d certainly like to help. As they get worse, they become increasingly insecure that Alex is going to get tired of their Friday nights in repeated ad nauseam; a slowly cooling pizza box open on the coffee table and two lips closed from communicating. The self-fulfilled distance this leads to results in a gradual, painful, desperate admittance of their romantic worries to Alex, who initially struggles to find the right words to help them, inadvertently appearing dismissive and deepening their worries further. Exhausted, she assures them she’s ‘learning how to deal with it.’

On one of many medication-fuelled restless nights, Alex’s wonderful self, unburdened by knowledge, sleeps by their side. A breaking point is reached. They wake her, wrenched from her blissful dreams and unawareness, and tell her how they’ve been feeling. The crushing experience of living each day like they are simultaneously the same as the last and could be their last. The fear that she’ll leave. Oh god, of course she’ll leave. Who wouldn’t.

She doesn’t, obviously. She loves them. Terror turns to confusion as she doesn’t start packing her bags, but instead attempts to unpack their struggles.

“So how can I help? What do you need me to do?”

Confusion turns to despair, as they find they simply don’t know how to be helped, even by the person holding their heart.

“I wish I knew how to fix this, but I don’t know that you can do anything. I think it’s something I just have to live with.”

Despair turns to comfort.

“Then I’ll live it with you.”

Comfort turns to confusion.

“I don’t know how you could possibly love me.”

Confusion turns to love.

“You don’t need to. Just know that I do.”

The loves I’ve had in my adult life all experienced my depression and ideation very differently. My boyfriend two years ago knew there was something rotten inside me, but that was all, and he wasn’t particularly able to help. Often I would be curled up on the bed in my overpriced university accommodation, knees to my chest, able to tell him something was deeply wrong, but never quite what. My partner one year ago, partly thanks to my own marginally increased willingness to actually open up, and their own willingness to listen, had a clearer understanding of the emptiness, but they still weren’t sure how to help.

My girlfriend of this year was suffering to a similar degree, so there were no issues in parsing and discussing what was drowning us; our sorrows may not have been halved, but they were lightened. We were open books to one another — open wounds, maybe — and we wanted nothing more than to help ourselves and each other. She was also an ocean and five hours away from me, my heart growing fond and cherishing situations like waking up at my 6am just to excitedly message her before the night took her at her 1am. Abdurraqib writes, with a bittersweet smile I have only come to understand from my own living of it, that ‘The thing about being in love with someone who does not live where you live is that the two of you have to think of new and inventive ways to see each other.’ Unfortunately, being in love and suicidal doesn’t make you capable of saving your love from suicide. If you’re standing together on the bridge’s safety rail, holding hands, it’s hard for either of you to pull the other back from the edge. We were wrecks before we crashed into each other. Still, we tried. We haven’t stopped trying, after moving from close friends to girlfriends to closest friends; we’ve never stopped helping each other, and I think we’re both better off for it. As in Baker’s half-wailed words, ‘We are gonna figure something out, if it takes me all night, to make it hurt less.’

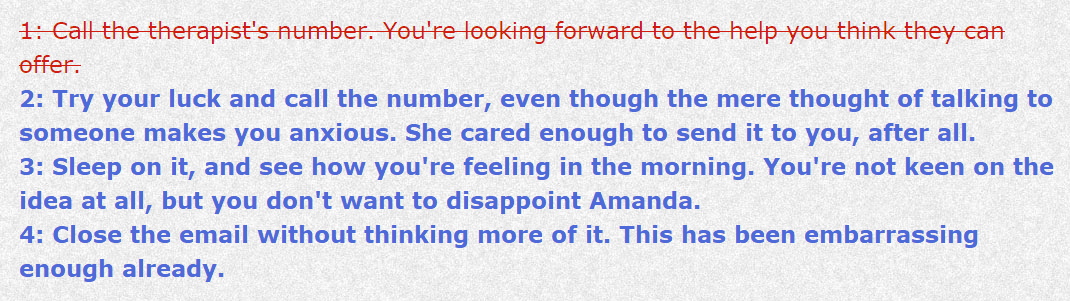

The hardest part of getting help is taking the first step. It’s close to a cliché at this point, thrown around with all the emotional weight of a ‘Hang in there!’ motivational poster, but it’s not untrue. The protagonist's own journey to starting therapy is as cliché as it is familiar — a friend notices their poorly-hidden distress, their hands shaking unconsciously around a coffee cup, and asks if they've ever looked into professional help. They deflect, reassuring their friend that they don't think it's that bad, and convincing themselves that they're not worthy of being helped.

I avoided the option of therapy for an irresponsibly long time in the same way I avoid most things that could be good for me: I curl up like cornered prey when presented with a path that could help me out of the comfort of misery, at the cost of said misery pooling and pooling, only realising I’m drowning once my lungs are half filled. Only when I was metaphorically — almost literally — gasping for air did I finally take her rightly insistent advice to reach out to a therapist; despite this coming from someone who has seen my vast soul, truly wants the best for me and was speaking from her own beneficial experiences, I had still been petulantly plugging my ears. A scared child who never learned to swim, refusing the hand trying to pull me from the depths.

Abdurraqib takes umbrage with the notion of your life — your past — flashing before your eyes in the precious seconds approaching death. He instead insists he saw his future ‘parading itself in front of me. All of the things I wanted to do, but hadn't yet.’ Death is your last stop, the cutoff point barring you from experiencing any more of the world, any more of your life's possible outcomes, any more dreamt goals and unexpected curveballs the future could pitch at your unsuspecting head. ‘Death is a bed of unkept promises.’

I have been in close proximity with the choice to snuff out my own flame a few times now. I once came so close that it was only a last minute change of heart that led to me buckling my metaphorical seatbelt back on, my frame shivering with fear, shame and regret. Whether that regret was in regards to my succeeding or not to extinguish myself is still not certain to me.

Mostly, I've been too much of a coward to commit to any mortal wounds. Instead I sit relatively comfortably as a kitchen knife — I already own it, it's the economical option even if less romantic — glides across my forearm to create some abstract form of poetry, line after line, just missing its text. Perhaps this essay is that text. I bleed and bleed but never lose enough to pass out, nor cut deep enough to pass away. It’s easier. It's repeatable. It's temporary.

When Abdurraqib writes ‘To unbuckle a seatbelt on a highway and to take a knife to your own skin aren't equal measures’, he is not advocating for or against either choice. It is no more and no less than a truth. A knife helps survive the nights I do not wish to see the sun rise. The blood spilled prevents a loved one from having to hold my motionless frame spilled onto a tiled floor. The scars left remind me that new days dawned whether I hurt myself or not, and I will still be here to feel the sun on my pale face.

Depression Quest’s epilogue posits that ‘all we can really do with depression [is] just keep moving forward.’ I can’t disagree. In time, I have gotten better. Somewhat. I’ve wanted to, which has been quite a change in itself. I no longer see death as an option, let alone a good one. The economical option more frequently loses out in favour of no option at all. Text is limited to characters on a page, not blood on a blade. I have started spending my Saturday mornings with a therapist. I spill my guts, not my ichor. ‘This year, I’ve started wearing safety belts.’

The possibility of falling apart is everpresent. My flame flickers often, more than I’d like. I struggle to hold myself together, close to shattering if I loosen my grip for just a second. But I’m slowly, hesitantly, with great effort, allowing myself to crumble when I need to. There are people willing, waiting, begging to catch me. And when I’m with them, I don’t have to think about myself, and it hurts less.

Stop Caring is reader supported and 100% free. Please consider subscribing or making a one-time donation to make more of this possible. All donations on this article go directly to the author.

If you are interested in writing for Stop Caring, please reach out via the email listed on the contact page or dm Artemis on Blue Sky.