Mother Loves You

Or, the last article I will ever write about my mother.

Content Warning: domestic violence.

When I was a teenager, I found faded, off-color photos of my mother and her college lacrosse team. They were tucked away in a yet-unpacked box in the corner of the kitchen. Always there, but always ignored. In the photos, she was smiling. So were her teammates, her "sisters" at the Academy of Notre Dame. But they were not her only sisters; my mother was the youngest of five siblings, and that was the reason my grandmother hated her.

Charitably speaking, "hate" is a strong word. But for my mother to say it to me as often as she did, it must have felt that way, even if my grandmother never said it aloud. It's the quiet that confirms it – the way my grandmother missed my mother's healthcare appointments, or forgot to buy her clothes. It's the “I'm done with kids" and "Birth control didn't exist in a Catholic household” that reveals the contempt. Neglect is a silent and dusty kind of hatred.

Is being forgotten the same as being despised? I don't know. I would have loved for my mother to forget me when she took my bedroom door off its hinges. It would be nice, I thought, when she dragged me across the upstairs hallway by my hair. It would have been more compassionate of her to pretend there was no eldest daughter to look after.

If only forgetting were that simple. It's been years since we last spoke, and I know she still asks other relatives to intervene and force me to come home. I know too much about her in general. I know she likes Carly Simon and the Rolling Stones. I know she loves Italian food, and eats sundried tomatoes straight out of the box. I know sunflowers are her favorite flower. I know she came home from school some days and saw her father blackout-drunk on the couch, drooling onto the floor. I know she did the same thing in front of me every year on Christmas Eve.

I also know that she thought playing Aerosmith while I was in her uterus would make me a genius. Jury's still out on that one.

"We are poor technology. The human body and brain? Too capable of storing clutter. Too desperate to hold onto things."

"One day, you're going to be a very hands-off parent," she told me once in the car, driving home with a row of potted chrysanthemums in the back seat. Bright yellow; not sunflowers, but close enough. "My mother didn't care. She was done with having kids by the time I was born. You probably think I'm a helicopter parent, so you'll be like her. It's like a pendulum — I go one way, you go the other! C'est la vie."

That, too – she loved the concept of France. I say "concept" with purpose here: She's never lived there, and visited only once. I never understood what it meant to her, to be suspended for years in a place that doesn't exist. Cute little phrases on monogrammed hand towels, Eiffel Tower plates and mugs. Wall decals that smell like licked envelopes. Vacation photos from Paris with faded orange timestamps in the corners. The dishwasher washed the patterns off the dishes, and the stickers curled off the walls with time. Water damage, three moves, and a sea of misplaced clutter swept the photos away.

But it wasn't just the tchotchkes and tacky souvenirs. The obsession must have been philosophical for her, somehow. A justification for a lived reality. When things didn't go my way, it was always C'est la vie. When she didn't want to apologize for hitting me? C'est la vie. But somehow, when things didn't go her way, it was the end of the earth. La fin du monde.

The first and last time I hit my little sister was on the way to high school. It was winter, six in the morning. I made a wrong turn. The snow was piled up so high that what should've been a three-point turn became a frightening, twelve-point polygon. She rolled her eyes and whispered something under her breath. My hand twitched. “Ungrateful," I thought. “I give you a ride to school every day, I protect you from our mother, I do so much.” I hit her.

I still remember the way she flinched, hiding her head behind her arms. When we finally parked, I told her, "Never again. I'm so sorry."

The walk down to my first class was a long one. Why did I do that? What was I thinking? I knew the answer to that part, at least. Ungrateful. I protect you from her. I feed you when she doesn't. I pile us in the car at midnight to get away from her, to keep us safe until she tires herself out. I saw my sister's frustration with my bad driving as undermining the entirety of our relationship as siblings; I weighed one incident in the context of thousands more, and in that broader context, I failed to separate my heartbreak from my hand.

Of course, fifteen years ago, I knew none of this. Only now can I really understand the fact that abuse is not random; it stems from context, from history. The urge to strike my sister came from being parentified by my mother. My mother's urge to strike me came from the neglect of our grandmother. Generational trauma is the passing of a torch: It is the sustaining of a cycle that burns every hand it touches.

"It is our fate to be bound."

Watcher steps into her story well after its beginning. She is unknowingly born into, and is the direct result of, centuries of unresolved heartbreak. We see this reflected in her frayed interactions with her Sisters, the clones who have also inherited the reality she lives in. The world is designed such that they are pitted against each other in ways they can't understand — Fixer's rebellion and need for control, Knower's heartless pursuit of survival, Healer's casual bitterness, Bang Bang Fire's proclivity for violence, and Watcher's own instability and self-righteousness all cause misdirected tension as they lash out against each other.

While the game does not imply the Sisters are siblings in a literal sense (they are, if anything, diverging versions of their creator), it connects them to one another metaphorically. Left behind without their ALLMOTHER, the Sisters must derive meaning from Her relics, and adhere to traditions they no longer have the context to understand. They quibble and bicker over interpretations of amateur poetry and elementary-school scribbles, over the methods through which they perform their assigned Functions, and over their own interpersonal relationships. Rather than being immediately part of these arguments or choosing sides, however, we behold their struggles as a third party, an observer: a Watcher, whose purpose is simply to learn history and witness its progression into an uncertain future. From this perspective, the Sisters' arguments and miscommunications seem at times petty, and at times heartbreaking.

The audience knows, perhaps, that this infighting does not serve them. They know that Watcher does not mean to harm Fixer, and that Watcher should not listen to Principal without question. They know that Principal has created a self-fulfilling prophecy in the idea that "it is our fate to be bound". They know that Iris was cruel to those around her, and know that a teenage girl should never have been made to bear the burden of humanity's survival. It is easy to look at the screen and say, "Why can't you guys just talk to each other?"; it is much harder to reckon with the shape and causality of these rifts, the static that separates Sisters from each other and parent from child.

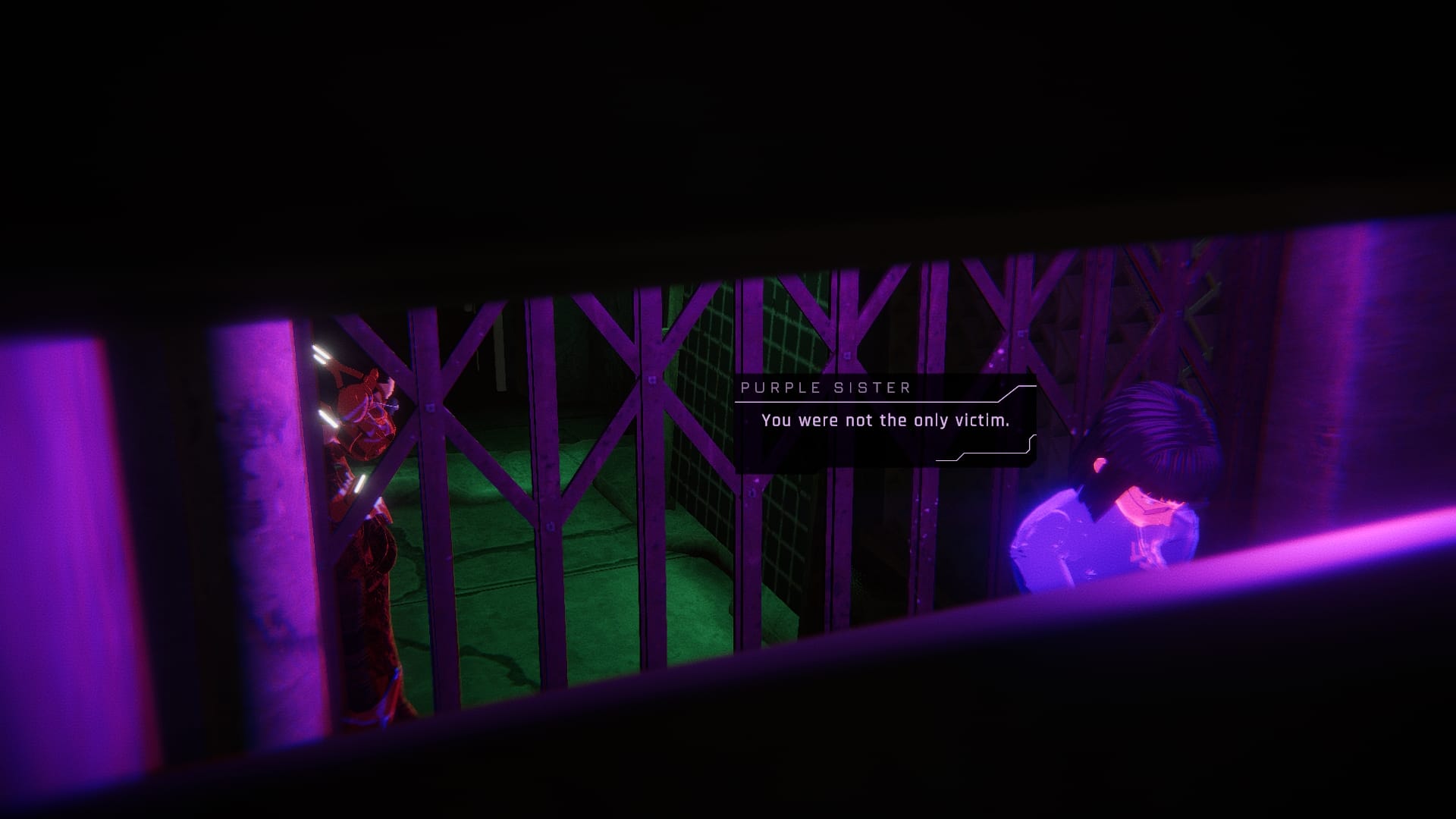

At the end of Watcher's first communion, in the low-lit hallways of repressed memory, she speaks with Fixer in secret. When Fixer confronts Watcher with a counter-narrative to everything she knows about the ALLMOTHER, all of Watcher's dialogue options in that conversation attempt to rationalize or excuse acts of cruelty.

Flipping through each choice hopelessly, trying to rationalize which one was the least bad, I remembered my hand striking my little sister. I heard my youngest sibling howling in my ears again, telling me that I could never understand how bad things were when I abandoned them by leaving home. I saw the two of them bickering again about who was "more abused", or who needed more help, or who deserved more or was owed more from life. I felt my rib cracking against the wall of the old, cramped apartment we moved into when I was halfway through high school. I smelled the residue of a lavender bath bomb at the bottom of the tub on the day I finally tried fighting back, when my mother got both of my siblings to hold me down by the arms. I tasted the cold autumn air of the last semester I spent in college before dropping out, expecting to hop on a train and disappear.

There are no clean-break resolutions for traumatized people. Every victory is hard-won, and every good outcome is detangled from the barbed wire of a thousand more painful ones. Our suffering is not necessarily community; too often, it is isolation. For about seven years after leaving college, I didn't speak to my siblings, and certainly not to my parents. I did not mourn leaving my parents behind. But there was not a single day where I stopped wondering how I could have done better by my siblings, about how if I were just smart or careful or kind enough, I could have kept us together in some more meaningful way.

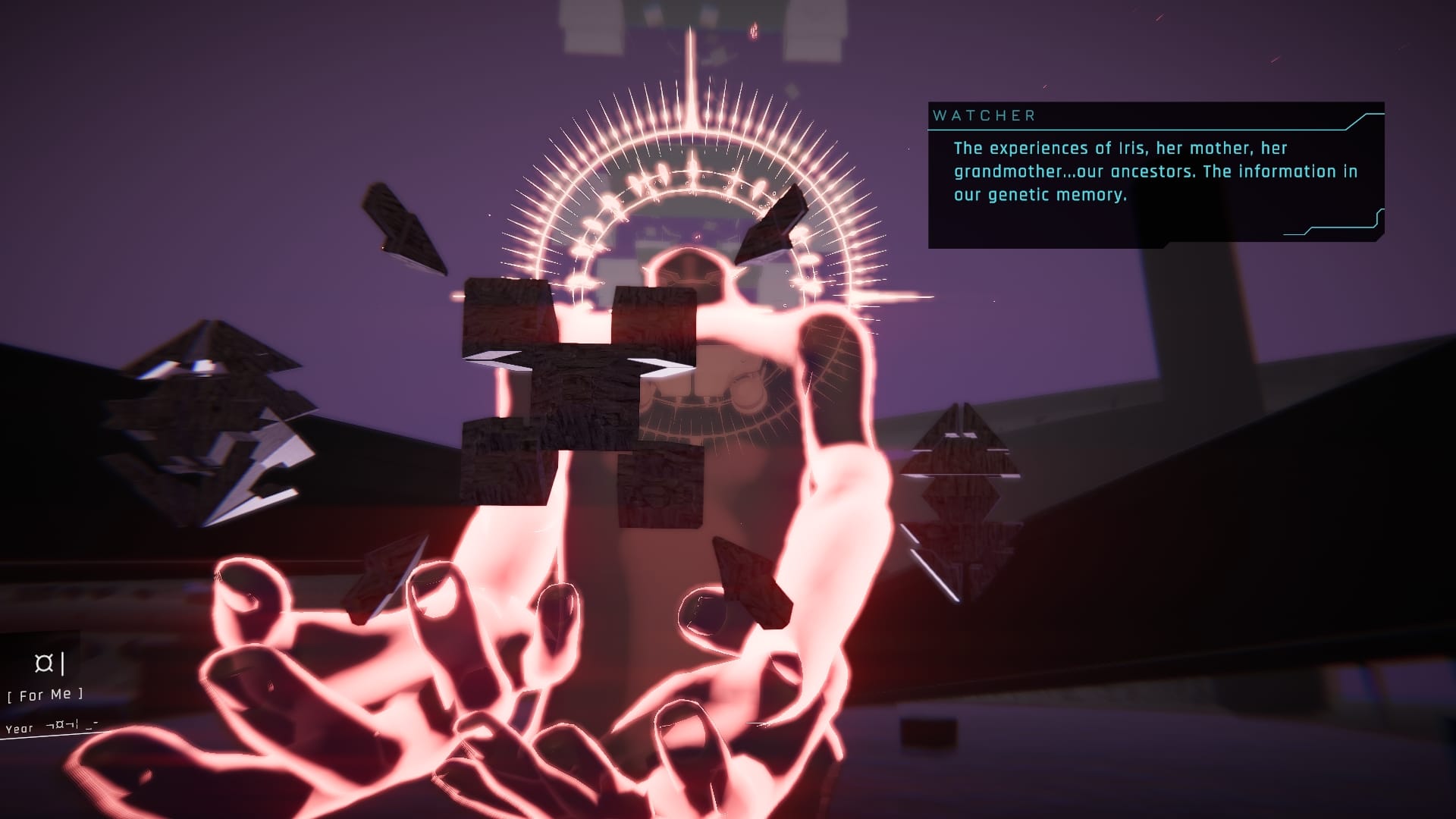

As we see the long, cruel arc of Iris' life prior to her miserable facsimile of godhood, we witness just how many little things set her up to fail from the beginning — the racism of her classmates, a subsequent disconnect from her identity rooted in self-hatred, the resulting fraught relationship with her own parents, her own inherited mental health issues, and her inability to connect with people around her even when they are genuine and kind. The game goes even further back than that, too. Iris carries trauma from her own mother, who struggles with C-PTSD and fits of sleepwalking brought on by flashbacks to her time protesting the occupation in Hong Kong. Further still, we see Iris' grandmother as a persistent shackle in her mother's mind, even two continents apart from her former life. Fittingly, she is at times represented by a disembodied answering machine: distant, but close enough to be one phone call away.

How can Iris hope to live a life that is truly hers, when the past chases her everywhere she goes? How can any of us move forward with the weight of so much suffering?

At its apex, the game breaks into a surrealist, in-between space. There, Iris reunites with her mother after centuries apart. They have their first honest, civil conversation in the entire story at this moment, when all the secrets of their lives have been laid bare. "We are poor technology," Iris' mother says. "The human body and brain? Too capable of storing clutter. Too desperate to hold onto things... you have to just move forward."

It is still true that Iris' mother beat her with a belt when she was a teenager. It is also true that Iris abandoned her parents at the end of the world, and wasn't there when her father took his own life. It's true that Iris' mother scared and criticized her harshly, and lashed out at her during the worst of her mental health crises. It's true that Iris, in turn, mistreated and criticized her best friend Jiao, and that she microwaved her pet hamster when she was a kid, and that she used an unearthly power to commit mass murder.

It's also true that here, in this quiet space, between red and blue, these truths were understood in the open. There can be no hiding from them, and perhaps no true resolution for them. But they are known and seen, their causality and cosmic origins revealed. And in that long, bending arc of suffering, two people can still understand each other with or without having to forgive each other. That one moment of acceptance—not necessarily perfect, clean forgiveness, but rather, the permission to truly move on—was everything I needed to hear.

"Sometimes, you just don't fit into the backpack."

While I cannot speak to the pain that Iris' family has faced as part of the soon-to-be Hong Kong diaspora, I am incredibly grateful to this game for the places where our experiences do overlap. These intersections foster empathy and understanding, and allow us to understand each other with all truths laid bare. Our history may be true, but it is not binding; our pain may be real, but it need not be inhibiting. I can understand my mother, but I do not have to forgive her. I can resent my mother, but understand that she, too, was part of a cycle beyond her control, a past with a dangerous gravity. I can look at those dusty photos of her college lacrosse team, and instead of wondering why she changed from this smiling girl into this cruel and bitter woman, I can smile back.

But most importantly, I can close the photo album and walk away. It is clutter left over from long-passed graduations and birthdays and unpacked boxes. Perhaps this history made me who I am, but it does not need to inform who I become. I have learned all I can to move on; I will not carry this.

Games are transformative in their power to turn history into living truth. Reckoning with cycles of trauma in a game gives us the agency to break them; what was once antiquated and distant from us becomes directly and immediately tangible through the act of play. On the global scale, 1000xRESIST weaves a history that stretches beyond us, envisioning a diaspora that does not yet exist, and imagining its liberation from grief. On the scale of my bedroom office, it gave me the knowledge and the strength to let go of what does not serve me. As it is for Iris, Watcher, and all those who come after them, letting go is necessary to living a life unshackled by pain. It is not our fate to be bound.

Or, in other words: this is the last article I'll ever write about my mother.

Stop Caring is reader supported and 100% free. Please consider subscribing or making a one-time donation to make more of this possible. All donations on this article go directly to the author.

If you are interested in writing for Stop Caring, please reach out via the email listed on the contact page or dm Artemis on Blue Sky.