All Paladins Are Bastards

The paladins in Crown Gambit, like real-life cops, can only make the world worse.

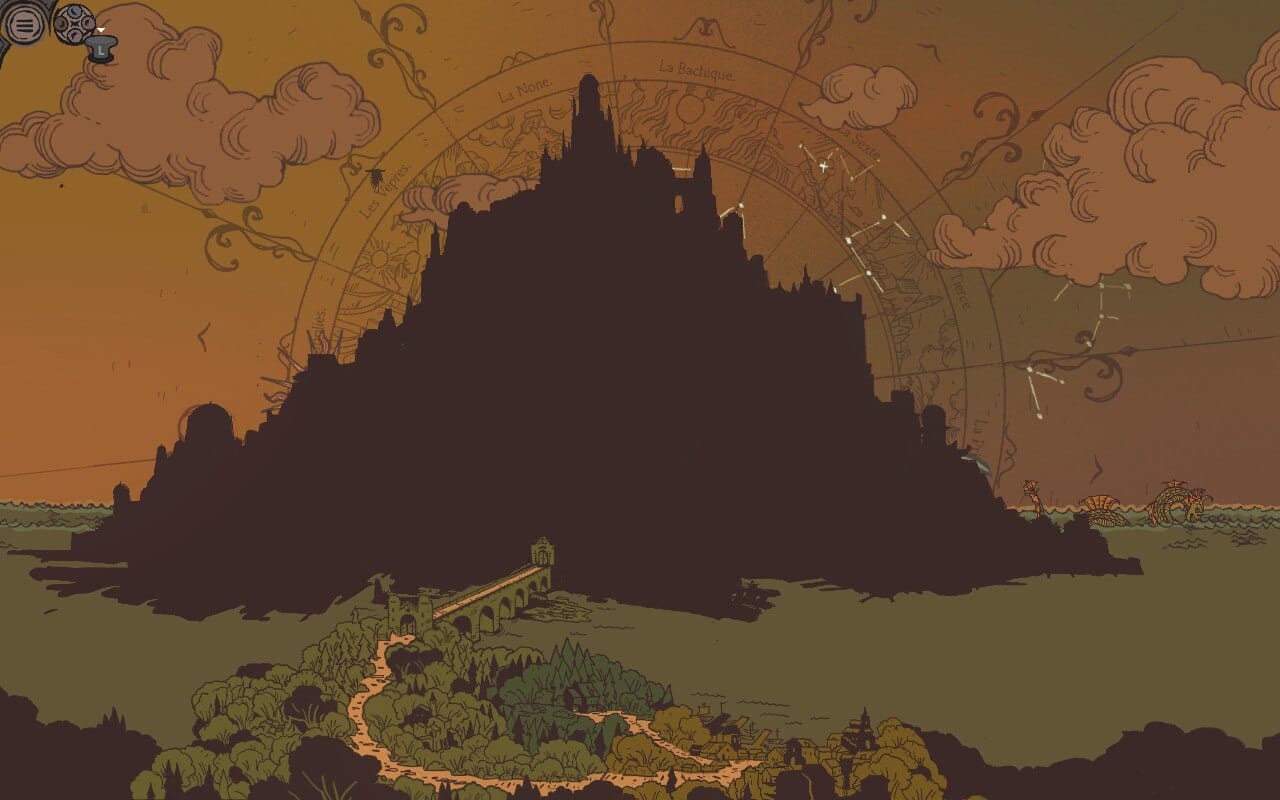

Mont St. Michel is one of the most fascinating pieces of French architecture and history. A massive abbey and castle that is sometimes surrounded entirely by water. Before modern bridges would be added, high tides would completely engulf the surroundings, turning it into a prime fortress. A perfect intermingling of religion and militarism from its inception in the 800’s through the following centuries. A spot supposedly called to construction by the archangel Michael, where pilgrims gathered, and a place to store soldiers and supplies while preventing enemy passage.

That image, a mighty castle surrounded by water, is clear inspiration for Crown Gambit, a card-based strategy RPG from French developers WILD WITS and publisher Playdigious Originals. This is Maerzön-Kastell, the multi-layered city that presides over the kingdom of Meodred. It stands on the main menu, first surrounded by verdant forest, but slowly, as the game progresses, the tide rises and rises. Because here, the tide is not a boon that will keep invaders at bay, unless you’re a noble who views the peasantry as invaders. See, the rising tide here is not habitual. It is rising higher than before and shows no signs of receding. Historically, the king’s blessed regalia gave him the power to halt the waves. But the king is dead. So nothing is stopping the oncoming destruction.

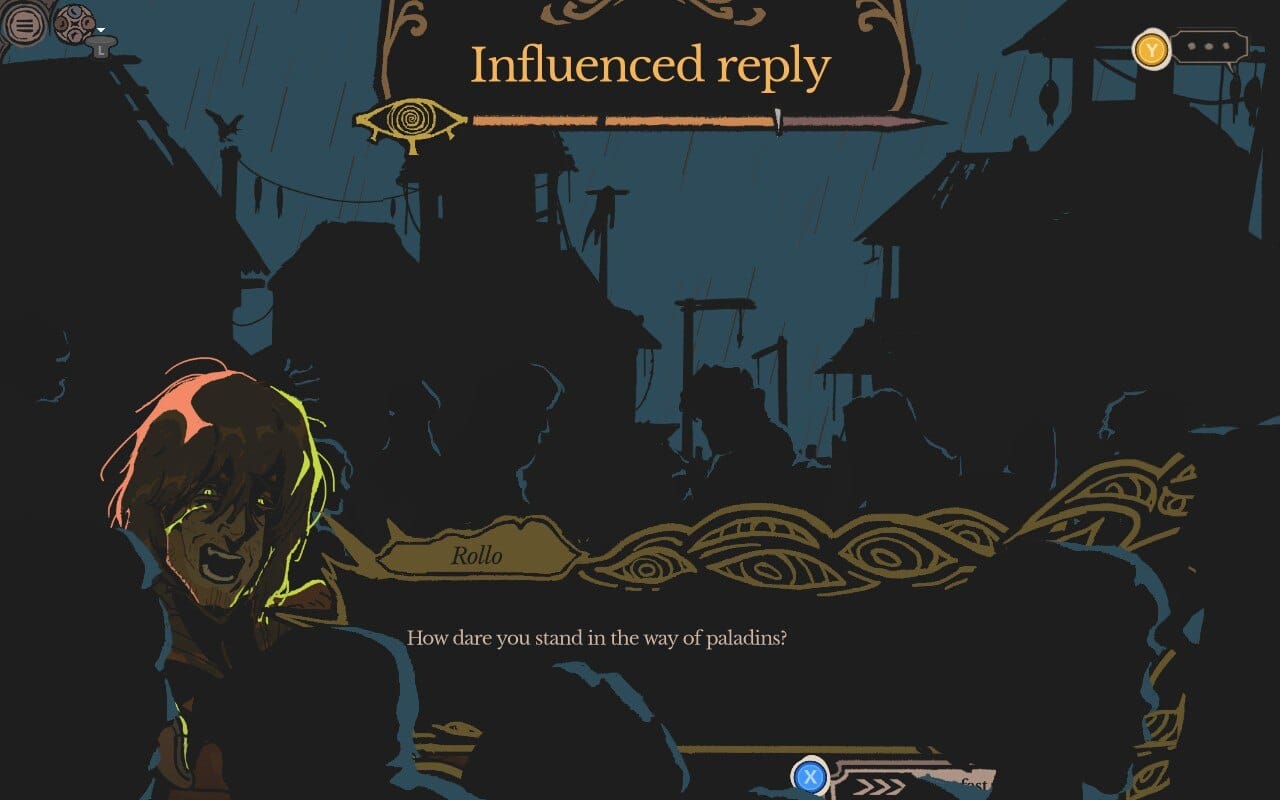

The king’s death was no accident. Assassinated by a shady order known as the Lanterns, in a small fishing town, traveling with the young crown prince and four paladins, knights of the realm, one veteran and three novices. Those last three - Rollo, Aliza, and Hael - are the main focus of Crown Gambit, the playable party that will carry out the missions. It’s through them that you get to commit some truly heinous acts to try and secure order. Oathbound figures, sworn to a union that serves the realm and the state, whose vows often mean throwing the people of the kingdom under the waves. When it comes down to it, paladins are cops, and all cops are bastards.

From the start, before the king has even been slain, the mission comes first. A random patron at the inn overhears the party’s identities and is summarily executed by Alphonse, the veteran paladin. Later, a similar choice is given to the party; an armored warden of the forest path crosses the paladins and, after a short battle against rabid dogs, can be put down to maintain secrecy or forced to take a religious vow of silence. The religion, the Order of the Ancestrals, is the only thing that can really change the Paladins’ senses of duty.

This makes sense. After all, the whole order stems from religious blessing. The ancient queen, Vermessa, established Meodred’s structure by divine power. She and all her descendants can wear the Crown of Azertor, which empowered and maintains control over items and weapons called Relics. These Relics in turn are what defines a Paladin; each knight wields one. Rollo’s anchor was given to him by Princess Gallenor, a commoner chosen by nobility. Aliza’s dagger comes from her own house, earned by being born into nobility. And Hael’s mace chose him by heavenly glow. Noble houses, useful assets, hands of god, chosen to enforce the rule of law.

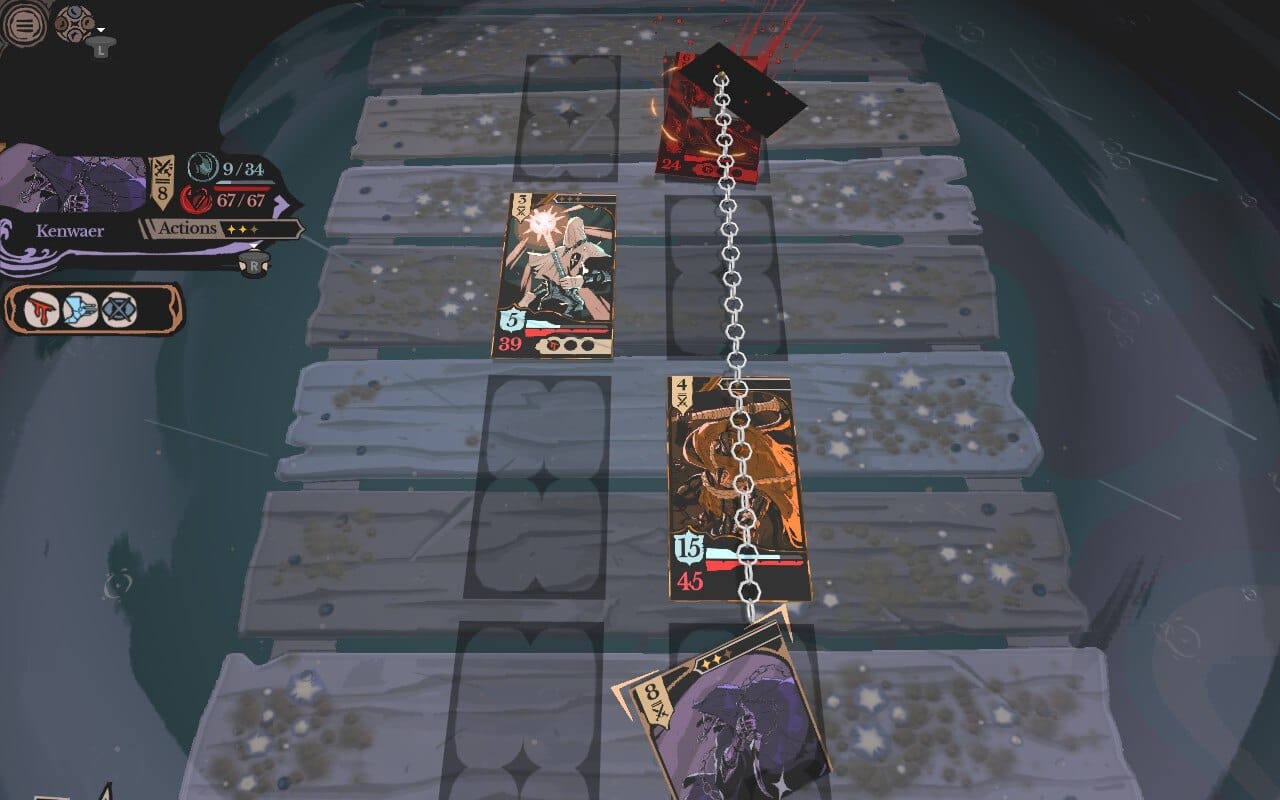

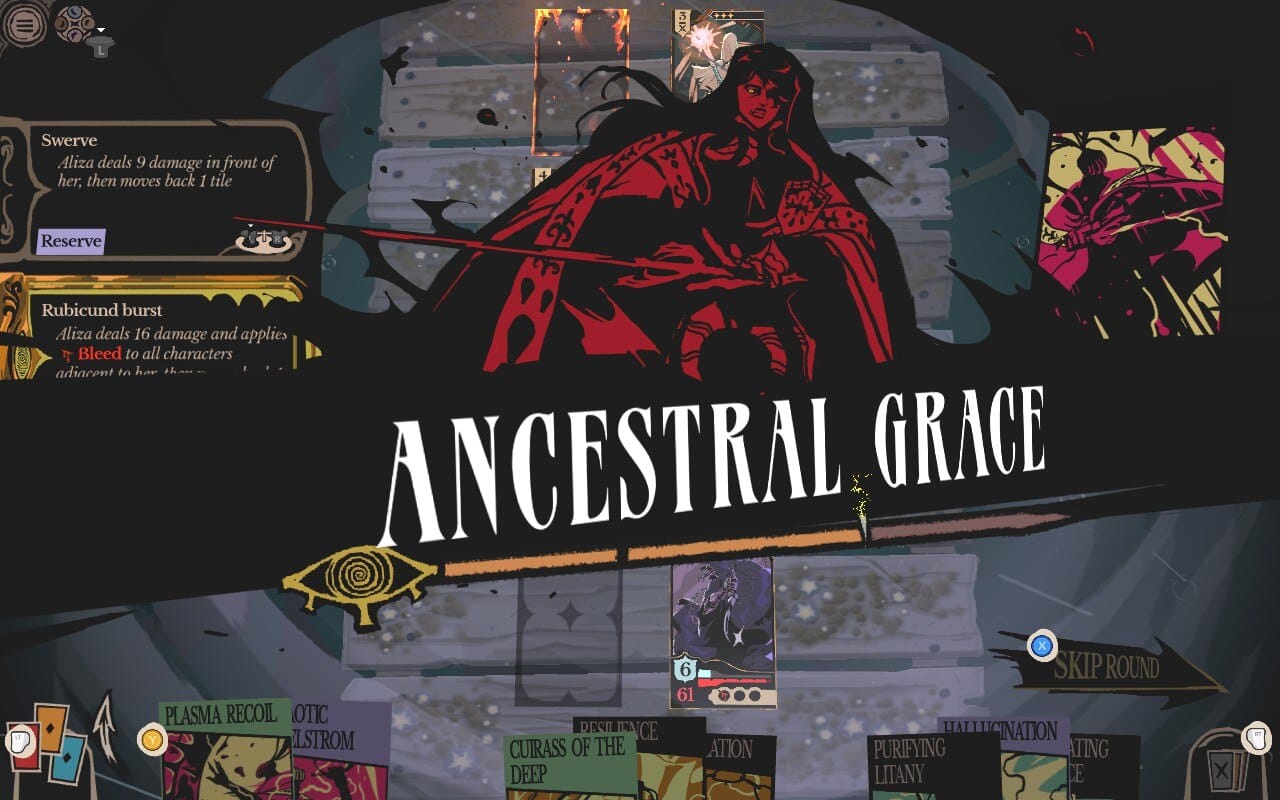

The Relics also have a chance to turn the paladins into narrative nightmares. Half of Crown Gambit is choosing dialogue and pathing, eventually picking a side in the war for the crown, but the Ancestrals can throw player choice off entirely. Each playable Paladin has a meter called the Ancestral Gauge, which increases when they tap into more powerful forms of abilities. If the Gauge is past certain markers, the Paladins will have bursts of outrage at key moments. Rollo starts a battle where you’ll kill tons of angry, innocent villagers right after the king’s death. Aliza lashes out at misogyny and sneering enemies, losing valuable connections and executing characters I wished to spare. While many of these moments are the Paladins pushing their own views into the open, some are directly antithetical to their own values. After defeating Gwinblyn, a Paladin who sided with the Lanterns, he begs for mercy. Hael’s decision here is to spare the fallen knight, but if the Ancestral Power takes Hael over, he beats Gwinblyn tortuously to death for breaking his oath.

If there is criticism I could have of the whole system, it’s that other parts of Crown Gambit aren’t quite punishing enough. Losing a battle just sets you up to restart it, so there’s not much penalty to losing. A lot of the difficulty can come from HP and Armor getting worn down over the course of many battles, since they only slightly recover after a fight, but they are fully restored at the end of a chapter. The Ancestral Gauge can be cleared by destroying the Relics of defeated enemy Paladins, with the drawback being a very difficult fight against a demon inside. But since Paladins are often fought near the end of a chapter, damage from the demon fight is quickly negated. Even when I played through on the highest difficulty, I was able to avoid any major disasters from the Ancestral Gauge.

Fortunately, the game has a compelling enough world and writing that I gave it multiple playthroughs to examine each way things could go wrong, helped by prompts that will show when a Paladin restrained themself. It encourages curiosity and pushing the buttons to see what happens. What will an Aliza who won’t hold herself back say when witnessing a husband treat his wife like a cruel piece of meat? Or Hael when someone blames the gods for the current calamities?

These outbursts are almost always violent, which makes sense. They are police. There is order and little room for rational discourse to keep the rabble in hand. Ignore that the people are on edge after a slaughter from years before the game, when the Paladins violently suppressed a riot. Or that now the corps itself is falling to infighting, allying with different factions and only causing more bloodshed for civilians. The tide is rising, people are losing their homes, and the royal guard is going to keep them from entering the safety of Maerzön-Kastell. Wood is being gathered in secret by nobles who saw the oncoming storm and are preparing massive arks to save those they select. Resources spent on what is seen as a pragmatic approach.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans police were given orders and authorization to shoot looters. While the infrastructure crumbled and powerless stores had products going to waste, citizens were not simply allowed to survive. The police exist to protect property, not people. In 2024, the NYPD deployed 800 police officers to New York’s subway to stop turnstile jumpers, resulting in an increase in pay and budget that far exceeded how much was “lost” by jumpers. It also resulted in more violence in the subway system, including an incident in September where the police shot four people. Over a subway fare. The same budget that goes to the NYPD could be used to make subways cheaper, if not free, but it’s not about the actual numbers. It’s about control.

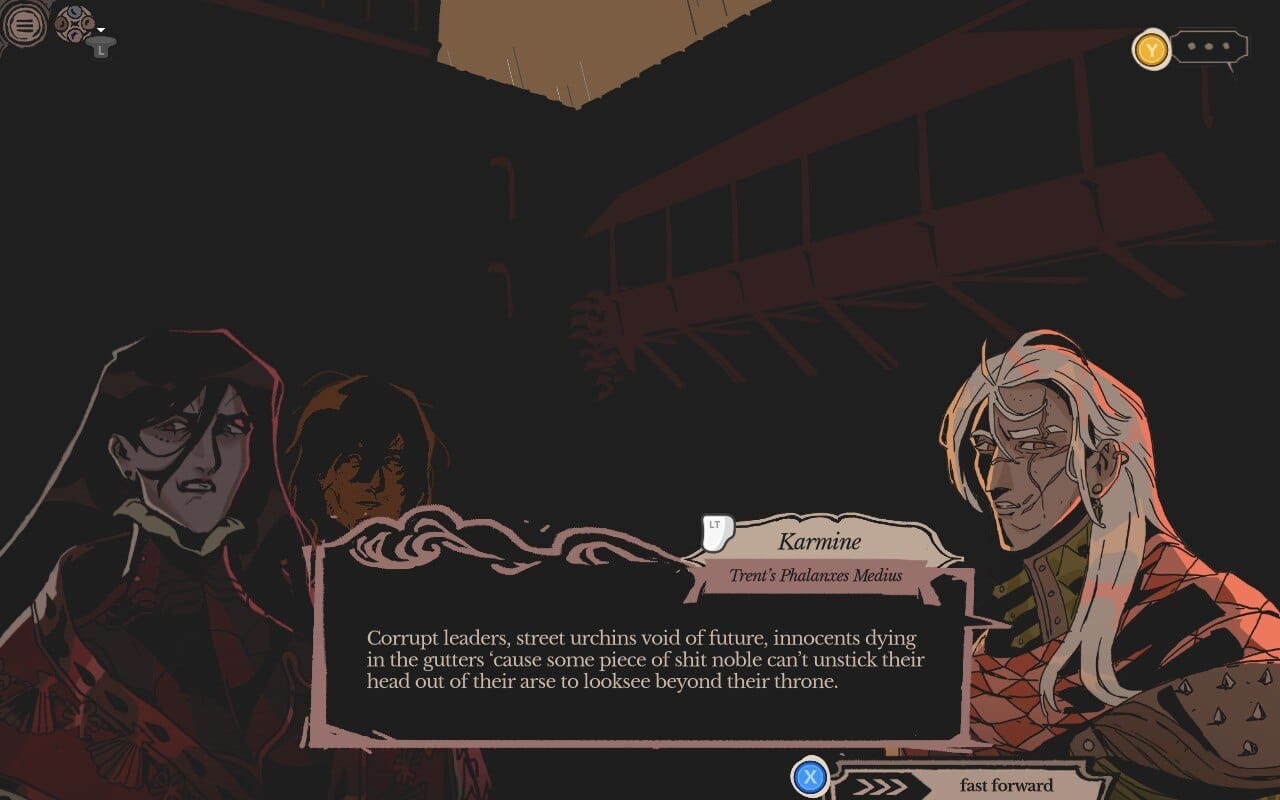

Other key figures in Crown Gambit understand that use of control. Contenders for the crown. The player can choose which is their ally, and by that very nature the others will be adversaries. Karv is the king’s brother and a high ranking official for the church; placing him on the throne will see a zealous theocracy. Havrok is a bastard son of the king, born outside royal marriage, whose violent uprising against the aristocracy is driven only by personal vendetta. Those with the best intentions may side with him, but actions such as killing his young betrothed to eradicate all control his father ever had over him show a short-sighted unity that won’t last. Princess Gallenor has been passed over merely for being a woman, yet, if she can be instated, is the opposite of Havrok. Reveling in opulence. And finally, there is Noamorad. He’s the firstborn since the King’s marriage, yet it is well-known that he is not the king’s son, illegitimately conceived. Even if the courts and gentry would acknowledge him, the Crown itself would not.

How then does morality and personality clash with the sense of duty? Each of the novice Paladins can easily find a side. Rollo’s commoner past can easily side him with Havrok, but he is also amorously devoted to Gallenor. Hael’s religious devotion naturally aligns him with Karv, while the misogyny Aliza has endured for years pairs her neatly with Gallenor…as long as she can get over the same privilege that she left her own noble house to avoid.

In the end, though, power is really in the player’s hands. Distinct dialogue boxes give choices of who to side with. The journey helps define where the player goes; my first playthrough ended up seeing the more horrible sides of Havrok and Gallenor, so I sided with Karv. But I also could have chosen one of the others before the end, including Noamorad.

This sort of player agency risks making the ending a bit too simple, but I go again to how the narrative itself compels. I felt the need to see each route through. And it also leads to the real thesis here: as long as you are a Paladin, you’ll be creating a worse world.

Paladins as a concept are well understood in nerdom through modern narrative, gaining major popularity in Dungeons & Dragons. They’ve always been one of my favorite classes. My first character - as a 7 year old playing AD&D while my dad DMed - was one. They’re often the noble knight. Often having “lawful good” as their alignment. That first half makes sense, but ever and always the alignment system easily falls apart with “good” and “evil”. Going out and vanquishing a camp of goblins is certainly seen as “good” by old D&D, but any modern examination should have no excuse to not acknowledge this colonial framing.

It’s also baked into the role. The term was specifically defined for the knights of Charlemagne. Not just any knights. These specific ones, in a story of divine calling. And justice. This small order is the focus of French epic The Song of Roland, named for Charlemagne's nephew and the ideal paladin. The poem revels in images of the crusades, with Roland and his fellow knights being the good Christian army against the evil Muslims. So reads part of the poem, as we first see Charlemagne and company:

“Not a heathen did there remain/But confessed him Christian or else was slain.”

This matches the first ending I got in Crown Gambit, siding with Karv. The ending roll describes him creating a bloody exodus for those who lack the faith. “The Paladin Corps was bonded to the Vestalis to hunt down heretics all over the realm,” the narration reads, all framed as if this was the right choice. As history would claim it to be. No matter how well-intentioned my choice to side with Karv was, I had chosen to create a fascist theocracy.

There is one way that things can go right. At least as right as they can. By ending the order of Paladins.

Noamorad cannot use the Crown of Azertor. He cannot be the true king. But he can help you destroy it, and, in doing so, nullify the power of the relics. It would mean the end of the Paladin Corps, and in a way ending what makes each of them special. Unsurprisingly, there are many who will try to stop this.

The greatest hope I have for this is to not only free the people from the long held rule, but also to free the members themselves. Some are beyond reprieve. Yet others are clearly stifled by the order. There are levels of queer coding throughout. When someone mistakes Hael for a woman, he says that he doesn’t mind. Silence, a potential foe at one point, hides her true identity from all except a few, such as Aliza. Other Relic users like Hermet, who can see layers into the future, are clearly driven mad by the same power they wield.

The beautiful art cements this. When there is dialogue, characters have their faces free and expressive. For combat, they don helmets and veils, becoming looming horrors, including the protagonists. It doesn’t matter how much Rollo struggles to provide for his bedridden father. Or how Aliza tries to help her sisters break free of their mother’s control. Or how Hael sees the church as an arm of charity. Because when it comes time to wield the Relics, to obey the order, to serve as cops while the coastline shrinks, it means covering their faces and becoming monsters.

Stop Caring is reader supported and 100% free. Please consider subscribing or making a one-time donation to make more of this possible. All donations on this article go directly to the author.

If you are interested in writing for Stop Caring, please reach out via the email listed on the contact page or dm Artemis on Blue Sky.